I’m going to tell you a secret about my office practice. (Yes, procedural-based doctors spend long hard days toiling in the office.)

On office days, I often play a little game with my imaginary friend. He challenges me to leave the prescription pad in the drawer for the entire day. The idea being that patients are on enough meds already, lifestyle changes are underused and the human body often heals itself. My buddy also warns me about making patients worse. That makes him mad.

I slipped up once and let a colleague in on my challenge. He was aghast, adding this: “John….cut it out…how are we supposed to help heart patients without medicines?†He didn’t mention the whole imaginary friend thing. Whew.

Let’s get a little serious about the paradoxes of using chemicals to treat disease.

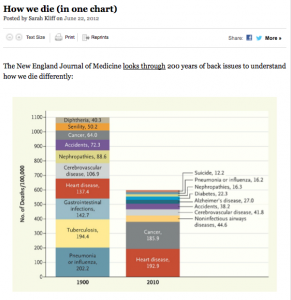

There is little doubt that medicines have improved mankind. Just look at this highly tweeted NEJM graph of how we died 100 years ago v. now. Much of the gain in lifespan has come from the beneficial effects of medicine.

There is little doubt that medicines have improved mankind. Just look at this highly tweeted NEJM graph of how we died 100 years ago v. now. Much of the gain in lifespan has come from the beneficial effects of medicine.

In many ways, I am a believer. There are some really good heart medicines. Here are three that stand out for their benefit, safety and depth of supporting evidence.

- Beta-blockers relieve palpitations, improve mortality in patients with heart disease and don’t generally harm people. I like beta-blockers because they might be the safest pill a human can take.

- We debate the benefit of statins in low-risk patients, but they are probably the most important medicine a patient with coronary heart disease can take. I strongly believe statins are one of the reasons why many of my ICD patients seem to defy their diseased hearts, and just keep on living.

- Blood-thinning drugs greatly lower the risk of stroke in high-risk patients with AF. Stroke ranks near the top of worst things that can happen to a person. Now we have three choices—soon to be four–of agents: warfarin, dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Though blood-thinning drugs increase the risk of bleeding, this downside can be minimized by patient selection and education.

Obviously, there are many more medicines on the list of “good medicines.†Doctors and patients are immersed in a sea of potentially good medicines.

The question is how much medicine is enough? Gaining benefit from medicines doesn’t add up like numbers on a spreadsheet. You can’t just sum the incremental benefits and risks. Drugs interact with each other. These are complicated chemicals that modify complex human biologic systems, often in highly individualized ways. That’s a fancy way of saying: modern medicine is not Mickey Mouse.

Many experts think we have gone too far in prescribing pills. They argue that patients are over-medicated. As a doctor on the front lines, I’d have to give this opinion significant merit.

The ‘Poly-pharmacy’ of American patients is not new. I learned about the dangers of prescribing too many medicines back in the 1980s. It’s just way worse now. That’s why I was drawn to this piece in the UK’s Guardian. Dr. Corey Franklin provocatively calls our situation an “epidemic of over-prescribing.” He nicely lays out three possible factors:

- Patients are increasingly burdened with chronic disease.

- Direct marketing to patients. Patients are made aware of drugs or diseases to “ask their doctor about.”

- Big pharma’s skillful and aggressive marketing to doctors. This includes the ‘employment’ of thought leaders who greatly influence prescribing physicians by speaking on behalf of the drug and then writing practice guidelines. (Think Multaq.)

I’ll add two of my own:

- Guideline and quality measure metastases. We all want to measure the quality of health care. In this way, doctors share the same fate as teachers. Policy experts wrongly think they can measure good doctoring by electronic compliance with guidelines (call them tests). So just like teachers are, doctors are measured by tests that rarely reflect skillful practice. This can lead to mindless testing and the need to get patients on ‘evidence-based’ pills. The huge problem here is that conventional wisdom in the practice of Medicine changes. What was right in the past can turn out to be wrong now. Medicine is replete with the hubris of conventional wisdom. Overly aggressive care of diabetics and the elderly with high blood pressure are two of the most recent examples of cracks in ivory-tower thinking.

- Disease creep. Another factor in over-medication is society’s acceptance of new diseases. I’m no pediatrician, but I do see a lot of young kids for high heart rates induced by attention-deficit medicines. My b-student brain wonders how many of these tachy-kids would respond to better sleep, exercise and good food?

If I was a professor of Medicine and not just a blogger, my bottom-line message would be simple:

Use the fury of medicine sparingly. Heck, you could even suggest a time out before writing e-prescribing a medicine.

Encourage patients to help themselves. Ask whether the slightly high blood pressure, blood sugar or pesky premature beats could be treated with simple and small choices. A pair of

sneakers is cheaper than the newest angiotensin-receptor blocker.

When I really dream, and not just talk with my imaginary friend, I often see doctors and educators and government and medical industry all working together to say—build communities where people can walk or ride a bike to school and work. I see a society where healthy behavior is normal and not an anomaly.

Enough dreaming. I’ve got to go doctoring.

JMM

13 replies on “How much Medicine is enough?”

Great post.

At a certain point, the use of drugs brings diminishing returns in terms of health of the population, especially as they age and begin to experience more adverse effects from drugs they cannot metabolize the way younger individuals do.

Thanks for a great post.

Peggy

Hey Peggy,

It means a lot to me to hear from you. Thanks.

I’m glad others are struggling with how much medicine to use. Gosh…it’s really hard out there–avoiding harm, yet still helping. That’s why I strive to empower the patient in the decision.

Options…Options…Options.

Odd that the author of the Guardian article calls Oliver Wendell Holmes an American physician. He was an attorney and judge.

I have a couple of family members who take beta blockers and they are well-proven drugs (for people who are actually sick) but they do generate many complaints about rapid weight gain and fatigue, not to mention impotence, brain fog, and elevated blood sugar and cholesterol levels that can lead to further diagnoses and medications. As with statins, if a drug prevents a particular individual from exercising I suspect the net statistical life expectancy benefit is much smaller than average. My husband was put on a high-dose beta blocker; his weight loss came to a screeching halt and he could barely stand without dizziness. After a year, when he was not suffering from either of his original problems, he cut down on the beta blocker on his GP’s advice but against the advice of his cardiologist, who doesn’t seem to believe either that a safe drug can have side effects or that a patient can ever get better. You don’t say so, but I bet you don’t blow off patient complaints about side effects in that way.

Correct.

I am especially sensitive to making patients worse with therapy. In fact, one of the great things about ablating arrhythmias is that it allows one to stop medicines.

A few sentences about the difference between side effects of a medicine versus toxicity. Beta-blockers may cause side effects related to blocking adrenaline receptors. These ‘effects’ stop when the drug is discontinued. In nearly twenty years of practice, I cannot recall a beta-blocker ever causing permanent harm. This is different than drug-induced organ toxicity. Obvious examples include: arthritis drugs that burn holes in the gut; AF drugs that induce cardiac arrest and cancer drugs that kill good cells along with the bad.

It’s all about managing risk: the risk of the disease versus the risk of the treatment.

That is true; I’ve never heard of ex-beta blocker users complain of partially irreversible problems as ex-statin users sometimes do. By the way, are you planning to write a column about the FDA delay on apixaban? Though my own loved ones fortunately don’t have need of it, I’m very curious. The only thing that is conspicuously fishy about apixaban is the fact that it wouldn’t have been much better than high-dose aspirin had apixaban not performed much better in those on high-dose placebo “aspirin” than in those on low-dose placebo “aspirin”. But there is, to us outsiders, no obvious reason to believe that the apixaban data are more biased or covered-up than the dabigatran and rivaroxaban data, and there’s no evidence of heart attacks or frequent gastric damage in the former. It almost looks as if FDA is refusing to approve the last and best merely because it would cut into the gigantic profits of the two already approved. If you have a reason to believe otherwise – or if you don’t, either way – that would be very interesting.

Never mind, he must be referring to Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., who was a physician. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was the Supreme Court justice.

Hope you don’t mind if I copy this article to present to my doctor who I’ve noticed lately is coming around to your way of thinking.

Don’t forget aspirin for the low risk afib patients

[…] [1] How much Medicine is enough? Dr. John M June 25, 2012 In Article […]

John,

You’re not the only one to play the “medication” game. Way back when I was an Internal Medicine Intern I had a weekly clinic. My goal was to take one patient off a medication at a routine visit… fighting the result of too many drug reps and “poly-pharmacy”. It’s an uphill battle… Enjoyed the post.

[…] [1] How much Medicine is enough? Dr. John M June 25, 2012 In Article […]

Hi John. Great, great post.

I’d like to play the role of devil’s advocate from a patient perspective regarding several issues in this post, and kind of enveloping another pet peeve topic of mine.

First, I agree with you wholeheartedly regarding your stance on taking the conservative, lifestyle approach first. I turned my lifestyle around 180 degrees after my afib episode, and vowed that I would do everything within my personal power to avoid having to be “treated” again. Without going into further detail (beyond the scope of this discussion) , let me just say that my own research led me to the conclusions I came to, and the changes I made. So far so good. I’ve managed to get off all of the meds, and my afib has not returned. I’m optimistic, but realistic, so I keep a careful lookout for any trouble.

I disagree with you on 2 points. You make a distinction between meds that are toxic to the organs, and those that are not. Let me submit that drugs can not only be toxic to the organs, but toxic to the mind and spirit. Sometimes the effects last long after the drug is discontinued. I know this from personal experience, and with family and friend experience. If I know a Doctor is taking some of the meds I’m familiar with, like beta blockers or Multaq, as examples, I would be very, very hesitant to go to them as a patient. Why? Because of the much under appreciated term “brain fog”. Judgement is impaired, mistakes are made, thinking is slow and disorganized. I would be afraid of poor and missed diagnoses. In life in general, in other occupations, the same thing can occur – you know, “don’t drive or operate heavy machinery”. Add to these effects depression, disorientation, loss of balance, and other similar things, and you have recipes for disaster. In the real world, these side effects are more dangerous than the minor annoyance designation they are given.

Sometimes I think that there ought to be a law (I’m being totally nonsensical now) that a physician be required to “experience” a drug before prescribing it to a patient – just to get a feel of what it’s like to experience the wonderful world of side effects.

That brings into thought the polypharmacy aspect of this as you nicely bring up – prescribing one drug to counteract the side effects of the first drug, and another to counteract the effects of the second. I have stories . . . . . boy, do I

My second disagreement regards the wonderful world of anticoagulants. Antecdotally, I’ve seen a whole different world than the fancy charts and stats that show how wonderful these drugs are, and compare the risks and benefits, and the comparisons within the drug class. I’ve known three friends to die from the direct effects of anticoagulants, one who is permanently disabled with anticoagulant induced stokes, and another who suffers permanent seizures and brain damage (a former brilliant individual now reduced to a very low level of life). I also know of so many people whose skin in ruined, who look like they’ve been battered and hit with baseball bats, who are relatively young, but look 90 years old, those who are afraid of doing anything remotely active for fear of falling, or hitting their head – scared of life, and those with permanent vision loss. As one person damaged by them told me “cardiologists love them – every other sane doctor hates them”. I personally do not know anyone who has had an ischemic stroke, including those untreated with anticoagulants for afib, but I know a lot who have been damaged by the anticoagiulant drugs. I think if you summed the risks of the drugs together, they would FAR outweigh the potential benefit. What I generally see in the nice charts and graphs is a direct comparison to only one form of risk at a time, like the risk of stroke vs the risk of bleeding.

Now, I know they have their place, but when I read things such as anticoaglulants are underused, and many more people should be taking them, I really, really wonder. Again, this is a patient anecdotal view. I guess it points out as much as anything why there is fear of them among patients.

. . . .which all goes full circle back to do whatever you canto change what you can to avoid having to be treated. “Better Living Through Chemistry” is a slippery slope crutch. I worry about some acquaintances with that attitude.

I’ve said my peace, and will now quietly exit.

Keep up the great blogs, John.