The British Medical Journal published a monumental study on screening mammography this week. It’s garnered a ton of media coverage because the findings provocatively question the sacrosanct idea that early detection of breast cancer saves lives. Imagine that…Imagine if the entire pink machine was misguided. Of course, for people who have been willing to squint hard and look through the haze of hype, this news does not surprise.

In two sentences, this is the story: Detecting disease earlier prolongs survival from that disease (you have it longer), but it may not improve the death rate. That’s because many of the early detections may not transform to severe disease, and because treating more people with potentially toxic interventions exposes many to potential harm.

Note that I specifically used the word disease, and not breast cancer. That’s because the same principle applies to other cancers, especially prostate cancer, but also heart disease as well.

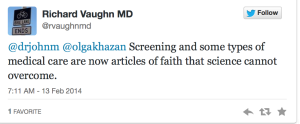

Rather than go on with my words, let me link a few articles and then you decide. Keep this Tweet in mind as you decide. Think past the emotionally charged issue of mammograms. Think about the larger issue of over-diagnosis and over-treatment.

Rather than go on with my words, let me link a few articles and then you decide. Keep this Tweet in mind as you decide. Think past the emotionally charged issue of mammograms. Think about the larger issue of over-diagnosis and over-treatment.

Dr James Hamblin, an Indiana University trained doctor, who is now the health editor of the Atlantic wrote this crystal-clear analysis of the BMJ trial. In Dr Hamblin’s article is a video from another Indiana University doc that explains (in John Green style) how improving survival may not equate to improving death rates. The bonus from that video is that it also explains how the Fox news dribble about British cancer care being substandard to ours may not be based in evidence.

The second article worth reading is this one from Dr Gilbert Welch. In it, he explains the limits of breast cancer screening and what we still don’t know.

The third and fourth works focus on one of the many dangers of early detection and treatment of cancer. Namely, the cardiac toxicity of cancer treatments. Over the past decade or so, as the pink campaign gathered steam, effectively squashing any voices of skepticism, an entire branch of cardiology came to be.

The field of cardio-oncology emerged to deal with the effects of radiation and chemotherapy. An article from CardioVascular Business (how apropos) chronicles the costs of surviving cancer.

And then there is this sobering review article in Circulation entitled, Cancer Therapy–Induced Cardiac Toxicity in Early Breast Cancer Addressing the Unresolved Issues. The vastness of that review article, and the fact that we have created an entire branch of cardiology to deal with medically-induced heart disease, makes you think hard about early treatment of anything.

This is important stuff. It’s not intended as anti-mammography or anti-chemotherapy.

It’s intended to make us all think about the tradeoffs of doing stuff.

JMM

12 replies on “The truth about early diagnosis — this is more than just a Mammogram story”

John! You write my favorite blog on the web.

It is so hard to convince people that more isn’t always better…so hard. Some deeply ingrained bias to “do.”

An anecdote to support the data –

My sister, age 42, just had a mammogram. Had a vasovagal (likely from the pain), passed out, had a head CT, cracked her skull in two places, spent a night in the hospita. Now, has a severe post-concussive syndrome, just had an MRI due to her severe dizziness and ongoing nausea. Had to drop out of her PhD program for a semester…

…all because of an innocent mammography – which she was coerced into doing by fear. At the age of 42 – when many are already wondering if it should have been done.

She was not provided a shared discussion.

So much work to be done.

Thanks Dan–for both the kind and helpful words. See my comments below on the use of fear.

Dr Miller is certain of his findings. Dr Kopans is just as certain that the study has fatal flaws. I know because I happened to be listening to Diane on my way home from a doctor’s appointment:

http://thedianerehmshow.org/shows/2014-02-13/new-research-value-mammograms

That sort of certainty tends to be nurtured by finding (Bending?) information that serves the favored hypothesis. So, who do you believe?

Should it come down to the prospect of life or premature death for my wife, I know which school of thought I would “tend” to agree with. Was the research done with outmoded equipment? Were the participating physicians adequately trained? Was it even double-blinded?

I don’t know.

How closely must you examine your own sources before you make up your mind?

Are you unbiased? Is it your life?

Jeff…I am really thankful you wrote those words. Bias is something I think about as I write about medical decision-making. Of course I am biased. We are all biased by the perspective of our own lens. The lens that I view healthcare through is one in which my main job is helping patients get the most benefit with the least harm–and there is a lot of potential harm out there. Many more times than not, I recommend stopping drugs, avoiding surgery and not doing tests that won’t change outcomes. (Some days I actually count prescriptions started v prescriptions stopped. It’s usually 1:10).

In the treatment of heart rhythm problems, a rule is that the greatest danger is often the treatment rather than the disease. Breast cancer, prostate cancer and asymptomatic coronary artery disease share many of these same issues. That’s not to say we should avoid treating, it’s just that there are always options. Patients need to share in the decision. And this brings me to another image from my lens. Namely, medical beliefs get ensconced, sometimes in the absence of compelling evidence. People, doctors included, struggle with idea that less is more. They struggle with the idea of not looking for early stage breast cancer, not putting in a stent because of a blockage, not irradiating a low-risk prostate cancer and not using antibiotics for every red eardrum. Why is this? Because they have been influenced by hype. (Often, well-meaning hype, but hype nonetheless.) And, as Dr. Matlock said, there is a deeply ingrained bias to do.

Doctors are susceptible to hype because many don’t have (or make the) time to look at the actual science–things like absolute risk reductions. Many clinicians wait for the experts to sort these matters out. Oh…but the experts have biases too. You don’t think you get to be president of a medical society by doubting things that industry provides, do you? You don’t get to be a thought leader in cancer therapy by questioning the pink machine.

Medical industry, which does a lot of good by the way, counts on the fact that regular people read headlines–not method sections of scientific papers.

This is why I am drawn to science and the scientific method. Read the actual trial, study the methods, assess the conclusions. Then give people the evidence in clear terms. Know your own biases; state your biases, share the decision, don’t be attached to a patient’s choice.

Sure that BMJ study had some flaws, all clinical trials do. It’s strengths, however, were in its simplicity and scope. 45K humans in one group, 45K in the other. Then at the end of 25 years, it’s easy to count the number of deaths.

The thing that bothers me most about many of the accepted dogmas of medicine, screening mammography is only one example, is that they are taken as law, as good health, as the right choice. Patients aren’t given choices. They are signed up for another mammogram next year. No conversation; no doubt is allowed.

That’s terrible because people have different goals, different perspectives on risk. Even worse: in a few years, some of these laws of good medicine prove to be not so good.

And one more of my biases: I despise, viscerally so, the use of fear in marketing and promotion of health products. I’m working through this one; it’s an ongoing struggle.

Thanks for the detailed explication.

As Average Joe, American Health Seeker, I’m with you. I’ve been the route of the “mandatory” investigation of an innocent “incidentaloma” which added quite a bit to my radiation total.

Yes, fear.

My concern, as Average Joe, is the fact that physicians are people also – as subject to momentary brilliance and humbling failings as I am. I’m in no position to judge the brilliance or the failings of my physicians any more than I am to judge the researches and trials that determine the protocols these same doctors do or do not rely on. My white coat syndrome kicks in every time because I know I don’t understand it all and I know I can’t be in control.

I try. My electrophysiologist is not the head of the clinic, he’s the one who does all the work. He answers all my questions. Seems to enjoy that challenge.

A comparison and an anecdote-

One reason to be wary of wide-spread guidelines is that it’s easy to figure out who to lobby. Science says mammograms could be overused? No problem – call your local politician and get insurance coverage for mammograms mandated. Problem solved, right?

Common core (in education) has suffered a backlash for much the same reason. Supporters say “How can you be against high standards for education?” Opponents say “Is it wise for one group to set nationwide standards? What happens when interest groups gain a foothold with the standards setters?”

Now, the anecdote.

A friend recently turned 40 and went for a mammogram based on the advice of her PCP. On the way out, she was told “You appointment for next year is on Month,Day.”

“I didn’t request an appointment for next year. Did my Doctor request one?”

“No”

“Isn’t there some disagreement on the need for annual mammograms for someone who just turned 40?”

“Well, we automatically make a next appointment for everyone who comes in. Better safe than sorry, right? Besides, it will be covered by your insurance!”

Two quotes from the website of that particular radiology group:

The debate is now over on when to begin annual screening mammograms. A landmark study published by the American Cancer Society (ACS) in 2010 proves annual mammography screening of women in their 40s reduces the breast cancer death rate in women aged 40-49 by nearly 30 percent.

The ACA health insurance reform legislation was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Obama on March 23, 2010. The ACA (also known as “Obamacareâ€) outlines the requirements for health plans to cover women’s preventive healthcare services, including screening mammography every 1-2 years for women 40 years and older, without cost sharing. Health plans are required to provide these preventive services only through an in-network provider.

You can search their website for hours, but you wont’ find a hint of nuance anywhere.

Another beauty. Keep it up. Thanks.

If the issue is between survivorship and mortality, I chose survivorship. I am all too aware that 30% of women diagnosed with breast cancer at any stage go on to develop distant metastasis. No one hides that fact from us. I am also aware that mammography is a fairly crude test. We really don’t have a better alternative. There are women who have unnecessary biopsies. Surgeons need to be urged to wait and watch questionable results. Women with small tumors that can be fairly well cured with lumpectomy surgery alone are demanding chemo and surgery and radiation. But for the woman who finds a cancer at stage 1 can avoid the chemotherapy and radiation that causes the late side effects. In women like me who had to choose between extending life with radical treatment knew we were choosing to possibly face life ending consequences of our treatment. But I was the single mother of an 11 year old daughter with no suitable home to go to if I died. I have needed the 10 years the treatments have given me even if the side effects caused a lower quality of life.

Women like me are every bit as responsible for the over treatment as anyone else. We take to the streets wearing pink tiaras and tee shirts proclaiming our sassiness and singing “I Will Survive”. Making it seem like we had a bad spell a few years ago and now we are happier and healthier than ever. Nothing is farther from the truth. But if women can be diagnosed in stage 1 rather than stage 3 or 4, they can avoid the choices I had to made.

I am happy to see cardio oncology emerging. I bet they are harder to find than EPs. But I always knew that there is nothing “safe” about chemo or radiation. It was only safer than allowing the disease to progress.

Great topic that has gathered increasing press in recent years (esp. with the controversy over prostate cancer screening). You cite an article by Gil Welch. I strongly suggest his book, “Overdiagnosis” – as a highly enlightening discussion of the screening problems you bring up. The book can be found here: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B004C43EW6/ref=rdr_kindle_ext_tmb (My understanding is that Dr. Welch donates royalties earned from this book). This is NO perfect answer. There clearly are some cancers that may be found early by screening that can be cured by early detection. That said – there clearly is much diagnosis from screening of diseases that never would have caused harm, but for which the treatments are far from benign. BEST policy- Let the patient be informed and allowed to choose what they feel is the best course for them with their physician (or physician extender) there to help advise if the patient has questions.

Hello Dr. John

Such a loaded topic. Already the opposing forces are lining up to take shots at the BMJ report, while the critics of overdiagnosis are quick to do the same.

I represent a demographic rarely heard from in this debate. Many years ago, a mammogram identified a suspicious breast mass deep in my chest wall – so deep that it required “quadrant resection” surgery to get to it, along with all the accompanying terror that only women facing a possible breast cancer diagnosis can know. Good news: the mass turned to be benign. I’d been “saved” by an early test and a brilliant surgeon. Bad news: I’d just undergone a permanently disfiguring operation to remove a harmless mass that would never have amounted to anything. Yet the only acceptable reaction to this scenario appears to be relief and gratitude.

This is what Dr. David Newman describes as “an important though uncommonly discussed issue in the translation of evidence from cancer screening trials, because it’s known that overdiagnosis and high false positive rates (misdiagnosis) lead to medical harms and unnecessary surgeries.” He writes more on this at TheNNT: http://www.thennt.com/nnt/screening-mammography-for-reducing-deaths/

Your mention of the cardiac toxicity of cancer treatments needs to be more widely understood as the tradeoff that they represent. Thanks for this.

regards,

C.

Thank you for sharing your insightful personal story Carolyn. This is indeed a “loaded topic” – with no perfect answer (but at least the “other side” is now being heard).

Unfortunately, more often than not it is our doctors who need to understand our increased cardiac risk. It is often blown off with statements like “the new treatments are so much better. There is only miniscule risk.” I’ve yet to have even one doctor

acknowledge it exists. It’s kind of like the myth that women don’t get heartdisease