Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation continues to ascend into the mainstream. The treasure of eliminating AF [symptoms] without taking pills stokes the demand for a fix. People like fixes.

Technological advances in catheters and mapping systems along with the formation of neural pathways (skills) in ablationists have fueled the growth of AF ablation. The epidemic of AF in our populace provides a never-ending supply of people in need. (One thing that has not contributed to the growth of AF ablation is reimbursement–nobody considers AF ablation “easy money.”)

Background on AF ablation:

When it comes to cordoning off the rogue circuits which initiate and drive AF (Pulmonary Vein Isolation–PVI), we have indeed come a long way in the last decade. What used to be an all-day, very scary affair, is now almost routine.

But we still have a long way to go before ablating AF could be called easy. Yes…more innovation would be well received.

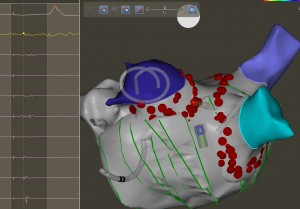

One such strategy for improving AF ablation involves using a better energy source to create electrical block. The current means for PV-isolation involves cauterizing the heart with radio-frequency (RF) energy delivered through a catheter. (See picture to the right)Â These point-to-point lesions form lines that block the passage of electrical impulses into and out of the pulmonary veins.

The primary problem with using RF as an energy source is that the lines of electrical block are not always durable. Leaks may develop weeks, months and even years after the initially successful ablation. Approximately one in three patients will require repeat procedures to “spot-weld” breaks in the electric fence.

To date, attempts to make the lines more durable, be it with higher power, larger catheter tips or other alternative energy sources, like high-frequency-focused-ultrasound (HIFU) for example, have all been limited by collateral damage.

So finding a better energy source is a very active area of research. We need the lines of block to be durable, precise, confined to the heart, and easy to make.

Could a laser work to ablate AF?

Perhaps…especially if you can actually see inside the heart to aim the beam.

The newest gadget for AF ablation that’s making news is called the CardioFocus HeartLight Endoscopic Ablation System (EAS). The Marlborough Massachusetts company describes it in this way: (from the Digital Journal)

…â€a unique catheter ablation technology that incorporates an endoscope and illumination to provide physicians with direct visualization within a beating heart, in real time and without radiation. It features a compliant, dynamically adjustable balloon catheter for improved contact with the pulmonary vein (PV) ostium and utilizes laser energy for more efficient, precise ablation. Recent data has demonstrated that approximately 86% of PVs remained persistently isolated after three months following a single procedure with HeartLight EAS, with 65% of patients achieving durable freedom from AF.â€

I saw the CardioFocus laser demonstrated during a live case presentation at the Boston AF symposium in January. The case was done by US doctors, but was performed in Prague. Hmm?

That said, it looked to be a pretty nifty device. The camera inside the heart actually lets you see the area of interest. Preliminary data suggest that the laser lesions may be more durable than RF. But let’s emphasize the word preliminary. There is clearly a lot about this technology that we don’t know; foremost among these gaps in knowledge is the safety of that pretty green laser beam.

Will the CardioFocus laser cause collateral damage to organs outside the heart?

We shall see. But after reading this month’s edition of Heart Rhythm there seems reason to worry.

In a small study from Hamburg entitled, Esophageal temperature change and esophageal thermal lesions after pulmonary vein isolation using the novel endoscopic ablation system, the CardioFocus system created esophageal ulcerations in 18% of cases. When compared to the thermal lesions created by standard RF ablation (15% of cases), the laser-induced lesions looked to be more intense. None of the patients developed serious complications in the follow-up period.

One could view these findings in two ways: the positive spin would hold that more intense thermal lesions in the esophagus may indicate a more thorough line of block. The opposing view would be that higher rates of ulcerations in the esophagus can never be considered a good thing.

This is the challenge of AF ablation: do enough to durably isolate the pulmonary veins, but not so much to cause collateral damage. It brings this axiom to mind:

AF is not an immediately life-threatening disease, don’t make it one.

Look for more news on the CardioFocus EAS later this month when the European Heart Rhythm Association meets in Madrid Spain.

JMM