The normal number of heartbeats per minute is a frequently asked question. People, especially medical people, like well-defined lows and highs. Parameters which can be assigned an ‘L’ or ‘H’ makes life easier.

Competitive cyclists immerse themselves in a sea of information. In our quest for weekend glory, we intensely study oodles of data–minutia like speed, wattage outputs, RPMs, torque, elevation gain and of course, heart rates (highs, lows, and averages).

As a heart rhythm specialist, I am often asked to see patients referred for low or high heart rates. We are asked to be the judge for what is “normal.”

The old school teaching holds that the normal resting heart rate is greater than 55 and less than 100 beats per minute (bpm). Maximal heart rates are estimated by the well known formula: 220 – your age = Max heart rate.

But the heart rate is unlike a lab value. It’s far more complicated. For starters, the heart is immersed in a bath of hormones, chemical messengers, pressure sensors and neural inputs. These moment-to-moment inputs provide critical information to the natural pacemaker, which we call the sinus node. Simple example are: adrenaline release speeds the heart rate, while firing from the vagus nerve (which occurs at rest) slows the rate. But it’s not that simple. Genetic factors also play a role in determining both resting and max heart rates. So does fitness and stress and temperature and a host of things.

Back to the main question: What’s normal?

Similar to many other matters of medicine, the “normal†heart rate requires meshing a patient’s symptoms, or lack thereof, age, history, exam and sometimes an ECG. Young people, athletic or not, may be normal in the 30 bpm range. Likewise, despite what you read in the NY Times, a resting rate in the 100 range may also be normal.

It’s the same with maximal heart rates: the commonly-used formula, 220 – your age = max rate, varies by as much as 10-20%. For example, the maximum heart rate for a 30 year-old athlete may vary from 160-210 bpm. One’s fitness correlates with sustainable power outputs, not maximal heart rate.

This wide range of individuality, or normal-ness, of heart rate makes it tough for patients and doctors alike. A heart rate of 40 might mean a pacemaker for some, while for another it would be normal.

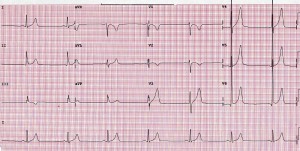

Here’s my normal ECG with a sinus rate of 40-something. No pacemaker for me.

Here are four simple thoughts to consider when heart rate questions arise:

- Make notes of your resting and maximal heart rates over time. Multiple measurements will give you and your doctor an individual fingerprint of sorts.

- Know that there is a great deal of individual variation of the normal heart rate. Keep in mind that many medical people don’t understand this great variation in heart rate. If questions arise, second opinions are always good.

- Not only is heart rate variation the rule, but it also true that greater turbulence of the heart rate is a good thing.

- A basic medical evaluation for an unusual heart rate is reasonable, but in the absence of symptoms or other associated medical problems, be cautious about undergoing invasive and risky medical testing.

- Remember this axiom: It’s hard to be make an asymptomatic person better.

What’s a normal heart rate?

That’s a tough one.

JMM

11 replies on “What’s a normal heart rate?”

Less many forget MHR can also be FHR (Fatal Hear Rate). over the years I have gotten into many a discussion of this subject and have had numerous folks try to pound in my head that 220 minus your age was a good baseline for MHR. I have always retorted with “If you want to possibly kill yourself then go right ahead”. The other argument I have frequently found myself in is that some people believe that MHR is a number that can be changed with proper training.I always try to dispel this myth and explain that they can become more efficient and raise their lactic threshold but that whatever their MHR is what it is. BTW since my ablation I have been unable to reach my MHR due to the fact that my heart rate climbs at a slower rate than in the past. This has also affected my ability to sprint greatly. Now I haven’t done an MHR test since my ablation but all my other numbers are right weer they have always been.

Excellent article.

We have too many people who promote myths, such as a heart rate that is automatically fatal, or too fast to be sinus, or too slow to produce good cardiac output. This only contributes to misunderstanding and mythology.

We need to stop listening to the people like Rich, who tell us that the maximum heart rate is fatal.

We need to start listening to people like Dr. Mandrola, who are telling us that heart rate is much more complex than, “If you see this number, you are dead.”

PS. I regularly get my heart rate 5% – 10% over my maximum while exercising. When I push myself as hard as I can, my heart rate will exceed 200. My maximum “calculated” heart rate is 170. I am not dead.

I do not recommend that Rich, or anyone else, attempt to imitate me – just as I don’t expect Dr. Mandrola to recommend that. As Dr. Mandrola writes, “To make matters even more complex, genetic factors also play a role in determining both resting and max heart rates.”

Understanding is much more important than rigid rules that discourage thinking.

Mr. Rouge,

Actually my MHR is a little higher than yours is (actual not calculated). I would argue that if you spend your entire life on the couch…then go out and push yourself to your MHR for a period of time it could be fatal. Those are the people I would tell that to. Also underlying, undetected heart problems + MHR could also be fatal. So in essence MHR can be fatal.

“Mr. Rouge,

Actually my MHR is a little higher than yours is (actual not calculated).”

I mentioned that my actual MHR is over 200. How do you conclude that your actual MHR is higher than “over 200”?

“I would argue that if you spend your entire life on the couch…then go out and push yourself to your MHR for a period of time it could be fatal.”

If you spend your entire life on the couch . . . then go out and exercise to 60% or 70% or 80% of your MHR for an extended period, it could be fatal as well.

Should we tell people to avoid getting their heart rate to 60% of MHR because it could be fatal?

“Those are the people I would tell that to.”

You told that to everyone reading the comments, here.

I would tell sedentary people to get a physical from a doctor and to exercise with supervision, since it appears to be something foreign to them.

“Also underlying, undetected heart problems + MHR could also be fatal.”

Underlying, undetected heart problems + a lot of things could be fatal.

Underlying, undetected heart problems + nothing could be fatal.

“So in essence MHR can be fatal.”

I could use the same argument to suggest that singing could be fatal, or showering, or studying, or a lot of other things beginning with “S.”

Does that mean that things that begin with S can be fatal?

People should learn to assess their level of activity, and their response to that level of activity, and not worry about any particular heart rate number being fatal.

thanks Dr. m for the article and for the clear thoughtful comments by all.

a lot of agencies are measuring fitness and rehabbing personnel using strict heart rate ranges. it seems a little too one-size-fits-all.

Is 48 too slow a heartrate for a 63 yr old not very athletic, but exercising regularly, male recently cardioverted and on Cardizem and Multaq?.

Verted,

Thanks for writing, but…These are good questions for your doctor.

Thanks. I have contacted my cardiologist. I was interested in the responses as it related to this discussion. I’m enjoying your blogs, and plan on reading as many as possible while exploring this crazy new world of afib I’ve been thrown into.

One additional comment. It’s a shame I don’t live within range of coming to your practice. As you have experienced afib, you have a good understanding of what we go through, and it would be a good doctor/patient relationship. Not that my relationship is bad now, but there are just some things hard to put into words when describing what’s going on within our bodies to give a fuller understanding to someone. I especially find it hard to communicate about medicine side effects to someone who has never taken the particular drug and experienced them. Ditto trying to describe my digestive system/vagal/afib connections.

As a parallel, my GP had been treating patients with gout, like me, for years, but it wasn’t until he had his initial attack of it that he realized how incredibly painful it was, and what we went through, and was able to fully understand what he was treating. He said it made a huge difference in his outlook on treatment and compassion for his patients.

It’s universally accepted that being a patient makes you a better doctor. Now even some medical schools are role-playing with students acting out what it is like to be a patient.

I too have felt the cold of the xray machine, experienced the long wait in the waiting room and the anxiety of the pre-op area. No doubt, these sensations help form the doctor that I am. Because those of us who care for people are people ourselves.