The thing about US healthcare that bothers me most is the waste: the nuclear stress tests on demented patients in diapers, the MRIs for every case of back and knee pain, the egregious pre-op tests for low-risk surgeries, the mega-workups for simple cases of AF, the disease mongering in the name of prevention, and most tragically, the replacement of simple bedside observation with expensive scans and labs. Hardly a day passes that I do not see at least one wasteful thing done in the name of good patient care. Not fraud, just extra stuff–the BS.

It’s weird; in the US we are used to spending a lot and getting a lot. But it is the opposite in healthcare. And so few seem to notice. It is as if wasteful care is becoming normal, like obesity.

It doesn’t have to be this way. There are things that can be done–together. The first step is seeing the problems that can be fixed. One is surely the nonsense–the waste.

Here are three recent exhibits of our healthcare system in action. I think they go together well.

The first exhibit is this Danielle Ofri NY Times piece entitled Adventures in ‘Prior Authorization.’ Dr. Ofri is an academic internist and a talented writer. She describes—as if it were new news—the consternation that all of us feel when we advocate for our patients by arguing with untrained cubicle people from insurance companies. She gets the maddening situation exactly correct. Namely it is this: I get that you, the insurance company, need to control costs, but I am one of the good docs, and this patient is doing well with an atypical regimen, so leave us alone.

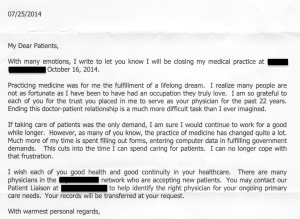

The second exhibit is this letter that a patient showed me. The retiring doctor is one of the best internists in town. She is smart, wise and compassionate. She was a leader in the medical community. She is not alone; experienced doctors are leaving in droves. Some are retiring completely, some are moving to administration, and some are moving to different careers.

The second exhibit is this letter that a patient showed me. The retiring doctor is one of the best internists in town. She is smart, wise and compassionate. She was a leader in the medical community. She is not alone; experienced doctors are leaving in droves. Some are retiring completely, some are moving to administration, and some are moving to different careers.

The third exhibit is this research letter in the Journal of the American Medical Association. In it, researchers reported an abrupt decrease in expensive nuclear stress tests after 2006. The distress comes when we think about why this would be. Likely factors include the publication of “appropriate use†criteria, enhanced insurance company scrutiny and a decline in reimbursement for nuclear imaging. None of these causes are flattering to us as a profession. First, good doctors should not need appropriate use criteria. Second, if you look at this data from the perspective of an insurance company (our chosen system), you can see why they badger doctors. Because it works. Yet the most disturbing reason for the abrupt drop in expensive testing is that reimbursement affected patient care. That is awful.

You can see how we (patients and doctors) are in this together. The angst described in Dr. Ofri’s lament is cumulative. Doctors can take these in the singular; but unremitting extraction of joy from the job is toxic. The inflammation builds to a breaking point. Then the people we most want in the system, the experienced, the wise, the caring, leave patient care. The plight of experienced doctors, therefore, is important. One might argue that a steady supply of young people will be available to replace the early retiring docs. Maybe. Maybe not.

So what can doctors do?

My obvious answer is leadership. We are the professionals trained to deliver care; we are the quarterbacks. One way we can lead is to have the courage to face the lessons of the nuclear-stress-test debacles. Of course we were doing too many lucrative procedures. The evidence is clear: in the last decade we have done fewer cardiac tests and procedures and outcomes are better.

But there is more to these stories than just misplaced incentives and greed. A lot of the waste stems from our lack of skepticism concerning the evidence. We were (and still are) too susceptible to hype; too fast to accept expert opinion. History teaches us a lot. We can learn from the botched dronedarone and dabigatran roll-outs, the niacin and non-statin-drug failures, and surely one could have predicted that stenting asymptomatic coronary disease would not improve outcomes–as if a wire cage could treat the systemic acquired disease of atherosclerosis.

The final thing I will say to caregivers is that even with the nonsense thrust on us, and there is a lot, we can still look up from our white screens and see and hear our patients. For if we do that, the solution is often in front of us rather than on an expensive MRI scan or a battery of tests. We can do better; I know I can. My friend, and healthcare leader, Dr. Jay Schloss offers eight useful tips for caregivers. His words are like an elixir for our inflammation.

What can patients do?

Caregivers are only part of the solution. Patients, too, have a role. The new normal is to be an active participant in making medical decisions. Patients should know that more testing and more care is rarely the best care. I realize that sounds like a big statement, but it is important, as much of what drives doctors’ decisions are your expectations.

I often tell patients that they don’t “need” anything I have to offer. Need is the wrong verb. Medical and surgical decisions are preference-sensitive. Yes, there may indeed be benefit from treatment or testing, but there also may be harm. There are always tradeoffs. That bears repeating: Always tradeoffs. The decision to get a screening PSA or mammogram has the tradeoff of possibly being exposed to unnecessary life-altering surgery. The decision to not discuss end-of-life goals with your loved ones and doctors has the tradeoff of possibly being exposed to death-by-ICU.

The final thing patients should know is that delivering quality healthcare is not at all about convenient parking or hospitals that look like luxury hotels. It is an American embarrassment that we fight about having enough money to cure Hepatitis C while we burn money on luxury accommodations in hospitals. You can help stop this outstandingly bad trend, as much of what drives healthcare policy is your expectations. In healthcare, convenience is overrated.

Reducing the waste. Changing expectations. Preserving the doctor-patient relationship. These are things patients and doctors can do together.

JMM

6 replies on “A letter to patients and caregivers — Improving US healthcare is a team sport”

I appreciate this letter. I believe it’s true, especially the parts about over-treatment, tradeoffs, evidence vs. hype, and luxury accommodations.

Would it be belching at the dinner table to point out that every single dollar of wasteful spending can be traced back to a Doctors order?

This paragraph jumps out at me:

“It doesn’t have to be this way. There are things that can be done–together. The first step is seeing the problems that can be fixed. One is surely the nonsense–the waste.

Upton Sinclair was fond of saying “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it”

That quote stings, and the same truth could be communicated with less force. I think the point remains.

Physicians seem hesitant to call each other out, for understandable reason. Working with frail, unpredictable, complicated beings (people), brings understanding of the phrase “there, but for the grace of God go I.”

Maybe it’s time for a change? Maybe it’s time to re-evaluate the Lake Wobegon view that all the Physicians are above average and all care is motivated by the good of the patient.

An economist, well versed in the power of incentives, would observe that our current health care system makes perfect sense given the incentives placed upon the actors.

Perhaps it’s time for the actors to acknowledge this? Many parts of our healthcare system, including many of the people, just aren’t working for the good of patients anymore – and it makes perfect sense.

Thanks Joe…

Your comments are terrific. I do respectfully disagree with you a little here. The root of the waste in our system is much less about dollars than it is about a culture of action, over-testing and over-treating. Sure, the financial incentives provide tailwinds, but the over-whelming majority of doctors are far from predatory (though even a few of these baddies kill our reputations). The problem I see, and try to communicate, is the culture. It’s not normal to tell patients that their disease is preferable to treatment; or time is often the best healer; or that simple antibiotic treatment puts you at future risk for really dangerous infections. It’s not normal to use a history and physical as the only test. It’s not normal to offer patients at end-of-life a conservative symptom control strategy. The default is chemo and surgery–or you could die, as if death is avoidable. So strong is this mindset that even if we went to a capitated or single-payer system, it would be generations before things changed. My wife works in the VA and she tells plenty of stories of over-testing and over-treating there. And even though I have always been conservative, the truth is that I probably did too much testing and treating in my younger days. You get swept up in it–b/c it’s normal. This is what I hope to change by writing about it. The change must come from both doctors and patients.

Thanks for the feedback. I guess the question becomes “Why is a wasteful culture normal?” My answer is because too many people (actors) depend on maintaining it.

In retrospect, I wish I had used the quote that replaces the word salary with livelihood. Incentives come in many forms, many more powerful than cash in your pocket.

Drug and device reps, office staff, maintenance staff, nurses – they all depend on the revenue generated by waste. Who wants to be the guy who orders fewer tests which results in someone else getting laid off? There is real social pressure – your kids go to school together…..

Drug and device companies repackage something common with a slight tweak and market the heck out of it for 10x the price. If it didn’t work they wouldn’t do it. We didn’t invent anything substantially new this fiscal year doesn’t pay the bills. Livelihoods protected…..

Hospitals – they do enormous good, employ hundreds of people, and some are the economic and social foundation of the communities they serve. Is there any doubt that even a 10% reduction in health care spending would cause tremendous disruption? Who wants to be the Exec who goes to the board and reports decreased revenues and less hours for employees but argues better care provided? Livelihoods protected….

Economically, healthcare has been one of the few segments of the economy where employment has grown over the past few years. Which politician wants to upset the local economy in their district by encouraging less healthcare spending. Livelihoods protected….

I could go on, but there are multitudes of people who find it in their best interest to ‘not understand’.

Nicely written.

It comes down to:

Needs vs wants.

Patients need skin in the game in terms of financial responsibility for outpatient procedures.

Patient needs and physician treatments must have their incentives aligned with the healthcare system in general.

There are way too many perverse incentives and malalignments in the system.

The worst thing to do would be to reduce competition and go to single payer. Instead create open competition amongst insurers without the govt backed crony atmosphere that protects their profits and overbearing overreaching regulations that punish doctors and patients alike.

Thx.

Both my office manager and cath lab manager have noted a drop in productivity for our group. We are doing fewer procedures. Surgery in the hospital is down too. The CMS released data recently that said health care expenditures are down. The causes of these declines are probably multiple, but surely the fact that people have more of their own dollars in the mix is playing a role. The question is what will this mean for societal health? My strong bias is that it won’t at all affect outcomes, or, it may actually improve them. I feel this way because one thing the US system is good at is getting the sick taken care of. If you are bad off, you likely will get care. Where we make our mistake is deploying that same fury on people without much disease or in those with such advanced diseases that it results in delaying death not prolonging life.

Somewhere along the line we became, instead of patients and doctors, consumers and providers. That right there sets the tone for today’s medical “industry”, and puts the whole relationship out of whack.

Selling CT scans at a discount for a “mother’s day present” is an outcome of this.

It seems to me that testing asymptomatic patients often leads to treatment, and treatment most likely will lead to drugs, which demand more testing, and treatment for the side effects, and the circle continues.

Treating by the numbers (think Statins) is an example. I’m sure there are many more.