Last week, I attended the American Heart Association (AHA) 2014 Scientific Sessions in Chicago. I was there as both a learner and physician-writer for theHeart.org.

Here are a few paragraphs on the meeting. The main purpose of this post is to introduce the five editorials I wrote. The links to the posts are at the end. A warning: I worked in the word asymptote. Grin.

I’m sorry to say the most-covered news of the meeting was hardly notable.

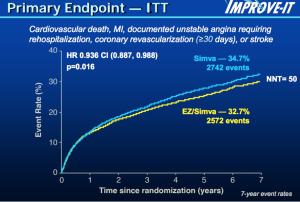

The IMPROVE-IT trial tested the combination of the statin drug simvastatin and ezetimibe (Vytorin) against simvastatin (Zocor) alone in patients who just suffered a heart-attack-like event. The results were headlined as moderate, but the number to needed to treat to prevent one cardiovascular event over 7 years was 50. That means 49 of 50 patients who took the drug got no benefit. The curves barely separated.

My colleague Melissa Walton-Shirley wrote the best summary on the trial. She aptly named the post: What I’m Telling Patients About Ezetimibe on Monday Morning. It’s really good.

Perhaps the most important result from IMPROVE-IT was that it kept the LDL-lowering strategy alive. Big pharma appreciated that, as the next line of health-thru-chemicals–injections of monoclonal antibodies called PCSK9 inhibitors–are being developed by multiple companies. Gosh.

Speaking of drugs and heart health, check out this Tweet.

A lecture on drugs at #aha14. Overflowing. People taking pics. The session on exercise is near empty. #TheProblem pic.twitter.com/hOjI9tfhdx

— John Mandrola, MD (@drjohnm) November 16, 2014

I made the above observation right after leaving a lecture on making physical activity and fitness a vital sign. In 20-minutes, Dr. Carl (Chip) Lavie (Oschner Clinic) made a compelling case that exercise and fitness are indeed vital enough to be a vital sign. Sadly, this session was nearly empty. It was a different story a couple of doors down where a drug lecture overflowed with attendees. This pattern–drugs to supplant lifestyle choices–will be a problem for future cardiologists. I’ve been here before so let’s move on.

On the way to my hotel, the taxi driver and I talked about the convention. He said the size of medical meetings was decreasing. I confirmed that fewer doctors were traveling to big conventions. For many reasons: the Internet; the rising cost of travel and dwindling corporate sponsorship, among others. The taxi driver came back with a smart comment: “Isn’t there value in connecting with your peers in person?”

Perhaps my favorite moment of the congress was meeting with two stars of the medical world. Prash Sanders is a professor, scientist and clinician in Adelaide Australia. He and I have become friends thanks to social media. Lisa Rosenbaum is a physician writer. Her interests are in how humans, doctors especially, come to make decisions. Lisa just took a job as a national correspondent for the NEJM. We also first met and wrote to each other online.

It happened that I was supposed to meet with both of them at nearly the same time. So rather than choose which friend to meet with, I said, what the heck, I’ll introduce the two. Here is the Twitter pic:

Great visiting w/ 2 rock stars of the medical world. @PrashSanders of Adelaide and @LisaRosenbaum17 of @NEJM #aha14 pic.twitter.com/l8h4XfIeLM

— John Mandrola, MD (@drjohnm) November 17, 2014

We had a great conversation. Not only did Prash and Lisa get along well, but their field of interests intersect. Lisa writes about medical decision-making and Prash’s work is utterly disrupting the decision-making of AF.

I’ve told you about the work of the Adelaide researchers before. They are showing that risk factor modification, much of it through lifestyle changes, may render AF (mostly) unnecessary. If millions of people with AF can be treated through lifestyle choices, what, then, are the ethics of burning or freezing their atria? Are we doing too many AF ablations? How do we help AF patients make choices that best align with their risk tolerance and goals? And, how do we–as a society–justify doing $100,000 AF ablations for a disease that might be treated by simple lifestyle choices? (Not in all cases. Please, fibbers, go easy.)

Lisa, Prash and I talked about other things as well. We touched on left atrial appendage occlusion devices, industry support of cardiology and the conflicts therein, writing, doctoring and serving the greater the good in different ways–as a doctor, writer and researcher.

Ok. Enough chatting. Here are the essays I wrote for Trials and Fibrillations.

The first day of AHA offered two choices for topics: resuscitation science or early career sessions. I picked early career. These were lectures for youngers given by olders–and they did not disappoint. The senior professors waxed philosophically on their careers and what lies ahead in the field of electrophysiology. There were beautiful moments in the talks. I actually felt a wave of emotion come over me during a Powerpoint presentation. Here is my report: Day 1 AHA: The Future of EP Is Not Bleak

On the second day, I found an abstract that looked at the relationship of AF burden and stroke risk. In terms of stroke risk, current guidelines do not distinguish between intermittent short duration AF (PAF – paroxysmal) and long-standing persistent or permanent AF. But that’s always been counter-intuitive. Here is the post: In Terms of Stroke Risk, Not All Atrial Fibrillation Is Created Equal. It includes the AHA abstract, and two similar studies from the ESC meeting in Barcelona.

Day 3 was a day for Big Data. Do you recall the Framingham Heart Study? This was(is) a three-decade longitudinal cohort study–medical speak for following patients over decades and studying associations. Framingham has shed oodles of data on cardiovascular risk, but it is a bricks and mortar study. What if we could do this type of research digitally? Dr. Jeff Olgin (chair of cardiology at UCSF) is the principal investigator of the Health eHeart study. He and his colleagues plan to connect people (a million is their goal) digitally and follow their health parameters over decades. Olgin told me they want to use this Big Data to predict heart attacks and sudden death–the holy grail of cardiology. Here is the post: Day 3 AHA: The Health eHeart Study: A Digital Disruption of Clinical Research.

My Day 4 post induced anxiety. It was a difficult essay to write because fear, marketing and corporate influence of medical leadership were central to the story. The specific issue involved the MagnaSafe registry, which studied 1500 MRI scans performed in patients with implantable cardiac devices, such as pacemakers and ICDs. MagnaSafe showed that nearly all cardiac devices, not just one company’s proprietary devices, are MRI safe. The post is Fear, Marketing, and Corporate Influence: Lessons of the MagnaSafe Registry.

On the plane home, I wrote a summary piece of the entire meeting. I talked about the incremental nature of cardiology in the current era. In a first draft of the essay, I included the word asymptote to describe modern cardiology and the limits of human biology. In other words, maybe we are approaching the limits of our humanity. If you read the post, AHA 2014: Inching Forward, you will note asymptote didn’t make the cut. This essay was a fun one to write because I was able to work in some less publicized but nifty studies.

That’s if for AHA. My next project is putting together a 2014 Top Ten Cardiology piece. I’ll be working on that in the next few weeks.

I’ll also get back to my What to expect after AF ablation list over on the DrJohnM Facebook page.

JMM

One reply on “Where is Cardiology in 2014? An AHA Review”

Regarding the apparent safety of conventional implanted devices in MRIs: the data presented so far look good but only address a portion of the safety issues. One of the things now known to those who follow literature is that 20 to 25% of implantees – possibly much more in some centers – will sooner or later end up with significant tricuspid regurgitation, with a high risk of resulting heart failure that, if treated inappropriately (i.e., by anything but explantation), will inevitably progress to worsening disability and death. MRIs may both heat up and physically move metal objects. Is there any reason to presume that none of the multiple mechanisms of valve damage could be precipitated or exacerbated by something the MRI does to the leads? These studies purporting to show safety have not done pre- and post-MRI echos. I feel that there is a sort of conspiracy to avoid acknowledging the frequency and consequences of this problem, because then it would have to go on the informed consent forms and more patients might start thinking, correctly, that it would be better to drop the metoprolol or amiodarone than submit to a pacemaker.