I do AF ablation. But, similar to my 2015 update, I continue to do fewer of these procedures.

What is new in 2016 is more confidence that this is the right approach.

My technique for ablating AF has not changed. I do pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) with point-to-point RF. Each burn takes 10-30 seconds, and at the end, the machine counts about 60-80 burns. If the patient has had atrial flutter, or previous heart surgery, or if I can induce atrial flutter, I will do a CTI ablation for flutter in the right atrium during the 45-min period of waiting to see if the veins reconnect. (CTI = cavotriscupid isthmus). I then check for other arrhythmia, such as PSVT or AT, often using isoproterenol, an adrenaline-like substance.

The first thing to say about AF ablation in 2016 is that there are no major technical advances. It’s basic PVI. Some groups use cryoballoon ablation. Don’t ask; I don’t know which technique is better. Probably the one your operator is most experienced with. There are a few labs, primarily in the US, using FIRM ablation, but two studies published last year failed to reproduce the original FIRM results. European physicians are skeptical of FIRM.

Another reason I do fewer ablations is that here in Kentucky, 8/10 AF patients I see have AF not as a disease, but as a manifestation of other diseases. These other diseases include obesity, sleep apnea, high blood pressure, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, excess alcohol intake or surges of inflammation–recent infection or surgery.

A 2016 development is that almost all experts believe these “upstream” diseases contribute to the milieu in the atria that cause it to fibrillate, and, treatment should be directed at these root causes. (I know many readers here don’t have these. I’ll get to that. Keep reading, please.)

I’ve discovered that if I aggressively treat upstream conditions, the person with AF gets better. Notice I did not say “AF”; I said “person with AF.” With risk factor treatment, sometimes the rhythm goes to regular; sometimes the episodes of AF shorten; sometimes the rhythm stays in AF but the person no longer feels bad.

The mistake cardiologists made in the past, myself included, was that we treated AF as if it was a separate condition. “Mandrola, this guy has AF; fix it please.” We treated AF with drugs, we shocked it, and we burned it. We saw AF in a silo; other than checking for high thyroid levels or valve disease, we did not search for its underlying cause. That was a huge mistake. It was like treating a feverish patient with bacterial infection only with Tylenol. We treated a symptom not the disease.

A new consult for AF is much more complicated now because it means searching for and treating the many things that led to the arrhythmia. And these other things are usually related to lifestyle.

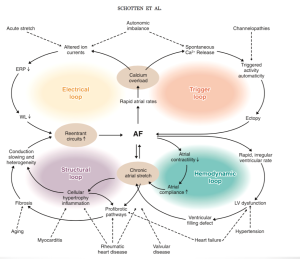

The picture to the right is a model of AF mechanisms taken from a review article (free) by Professor Ulrich Schotten and colleagues. Tell me where to put a catheter in that model. Look at all the factors that go into AF.

The picture to the right is a model of AF mechanisms taken from a review article (free) by Professor Ulrich Schotten and colleagues. Tell me where to put a catheter in that model. Look at all the factors that go into AF.

The good news is that if you treat these other diseases and risk factors, and the patient remains in AF and symptomatic, ablation is much more likely to work. That’s key, because AF ablation is a big procedure, and it comes with significant risks and costs.

Patient selection, therefore, is another reason I do fewer ablations. I have done ablation for 19 years, and ablation of AF for 11 years. Unlike referral centers, I’ve followed these patients myself; I’ve watched what happens after the procedure. With that experience, plus this new knowledge of AF, I no longer do cases that won’t work. I’m fortunate because I am older, established, busy enough, and thus, I don’t feel external pressures that a younger doc might feel.

Doing fewer PVI procedures does not mean not caring for patients. There are lots of things you can do to help people with advanced forms of AF. Many have excessive heart rates; that can be fixed. Many have sleep apnea; that can be treated. Many have not been told that they can exercise and get fit; correcting that misthink helps–a bunch.

I’ve also learned that extracting fear may be AF’s most potent therapy. Words and knowledge are powerful.

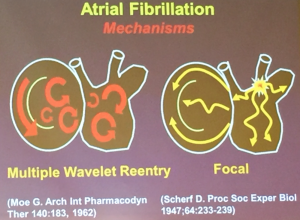

The reason there are no advances in “curing” most forms of AF is that we don’t yet understand its underlying mechanism. Experts still argue about whether AF is random or hierarchical. See the picture shown by Dr. Ed Gerstenfeld in a recent lecture; look at those dates!

The reason there are no advances in “curing” most forms of AF is that we don’t yet understand its underlying mechanism. Experts still argue about whether AF is random or hierarchical. See the picture shown by Dr. Ed Gerstenfeld in a recent lecture; look at those dates!

The other problem with AF is classifying it; focal AF, the kind that many of the readers of this blog have, is different from AF due to longstanding risk factors. Patients with AF must have treatment tailored to their situation. There is no one-size-fits-all in AF care.

Now a note for those of you who have AF not associated with a (known) correctable cause.

In 2016, I often encourage symptomatic patients who have forms of AF that I feel may be amenable to PVI to consider letting me do the procedure. I may say, “yes, I know that I sound like a roofer telling you need a new roof,” but PVI may help you.

I’m careful to discuss the life-altering risks of the procedure, which are low, but not zero. I’m careful to explain that the procedure is elective, and 100% preference-sensitive. No one needs an AF ablation.

I’m damn careful to extract fear from the decision. Patients with AF should never have ablation because they fear AF; it should be because they seek a better quality life. There is no compelling evidence that AF ablation reduces the risk of stroke or death. (Those studies are being done now.)

I explain that durable PVI may take a second “spot-welding” re-do ablation. If a patient is upset that AF came back after one procedure, I consider that more a failure of communication than of the procedure.

Finally, I will close with the most important take-home: The decision to ablate AF should be a slow one. This is an invasive procedure done in patients who are symptomatic but in no immediate danger.

True informed consent is critical. Second and third opinions should always be encouraged.

JMM

P.S. I receive many emails from patients. I’m honored that you tell me your story. And I’m grateful for your supportive words. But I cannot advise you medically without a real patient-doctor relationship. I am also closing comments on this post.