The purpose of this post is to introduce my latest column on Medscape, which is linked at the end.

You might wonder why an electrophysiologist is interested in cancer screening. I am interested because it may be one of Medicine’s largest reversals. A reversal happens when something (testing or treatment) doctors did, and patients accepted, turned out to be non-beneficial.

My friend Vinay Prasad wrote a book on medical reversals. It’s called Ending Medical Reversals, and it’s an important read.

Think about cancer screening as it is today. Millions of healthy people are told they should have mammograms, PSA tests and colonoscopy. Doctors call this health maintenance. People (notice I did not use the word “patients”) fear cancer, so they accept the invasions of their bodies. News outlets carry stories in which someone is either saved by screening or felled by late-stage cancer–because it was not detected early. The idea of cancer screening becomes entrenched as fact.

I was shocked to learn that there is no evidence that cancer screening works. I know that statement makes me sound like a nut. Let me explain.

Why do we get a screening test? We get it done because cancer is a common cause of death, and it is best treated early. We aim to prolong our lives.

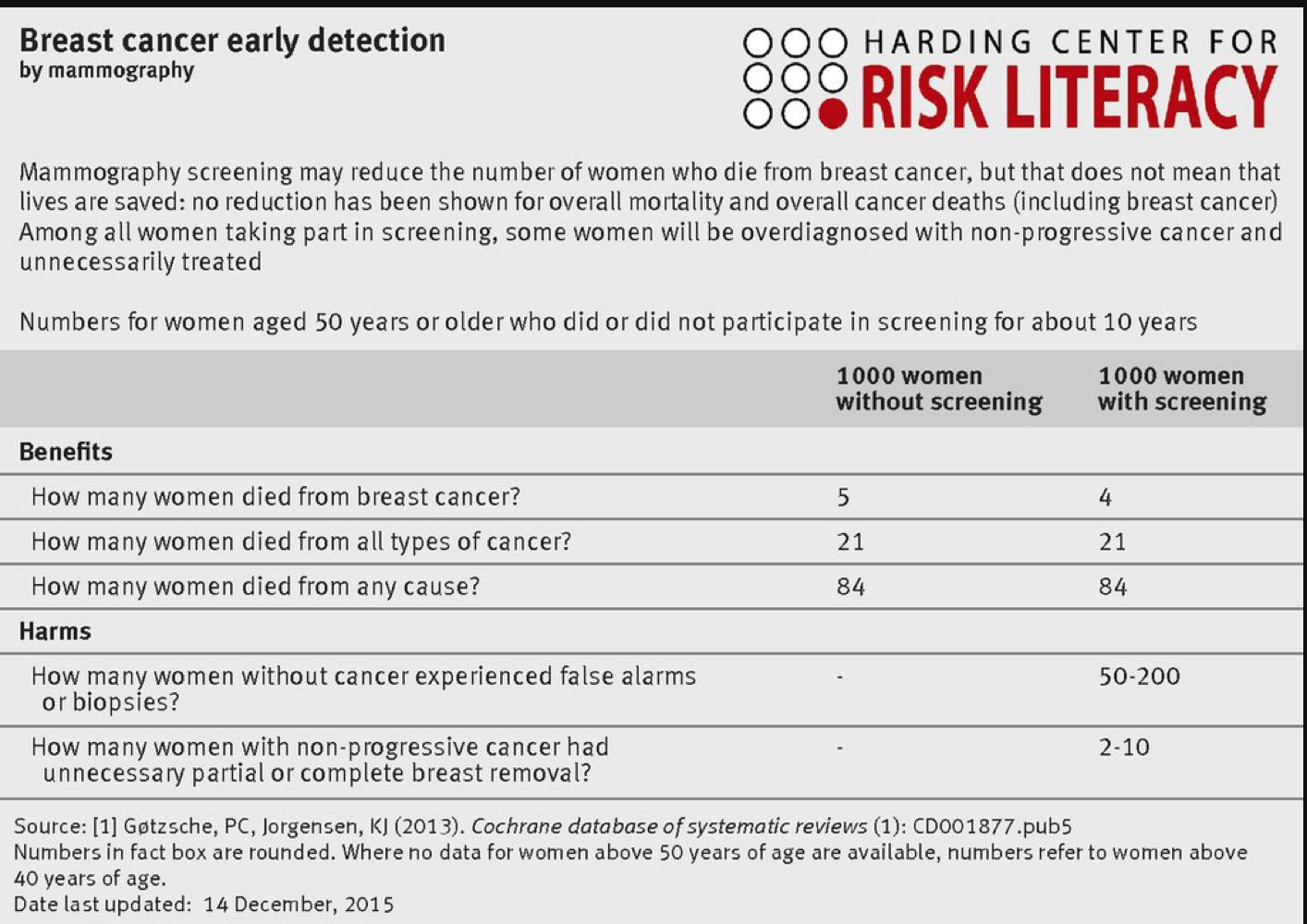

It turns out that when overall death rates are measured in those who are screened versus those who are not screened, there is no difference. Look at the mammogram graphic taken from a Cochrane Database review. See the third line down: “How many women die from any cause?”

It turns out that when overall death rates are measured in those who are screened versus those who are not screened, there is no difference. Look at the mammogram graphic taken from a Cochrane Database review. See the third line down: “How many women die from any cause?”

It’s the same.

And it’s not just mammography. Three authors, writing in the British Medical Journal, found similar results for colon, prostate and lung cancer screening–no change in overall death rates.

The problem lies in endpoints. Some of the screening tests do indeed lower disease-specific death rates, that is, a mammogram may slightly lower the rate of death from breast cancer. But that does not translate into a longer life. It’s the same with prostate and colon cancer screening.

Why would lowering the rate of death from a specific type of cancer not translate to longer life? Why would so many people look away from the evidence? What should we do about these revelations?

Take a look at my column: In Cancer Screening, Why Not Tell the Truth

JMM

10 replies on “Rethinking Cancer Screening”

I agree that medical decisions should be founded on science and data and proof. I too am surprised/disappointed by the findings of this research. However, my first reaction is not to dismiss screening absolutely as useless, but to understand why screening does not increase mortality with an eye to improving the screening process. For example, why not improve PSAs to reduce their associated increase in mortality. Why can’t relatively low risk saliva or blood tests be developed to screen for certain cancers? We can and must do better. But it’s very concerning when there’s a broad suggestion/recommendation that the elimination of cancer screening makes sense.

Superb column! I can’t understand why Medscape hasn’t sacked you yet – and I remain hopeful that you are working on a book, along with your many other activities!

Great column. Excuse my naivite (I haven’t read the studies), but the issue is with the current therapies–not the screening tests, right?

Apparently, our current therapies do not prolong life, but unless we test new therapies on newly dx cancer, will we improve? If I have a new drug that will cure 99% of breast cancer, everyone will get screened, and we wouldn’t have this discussion. Without screening, it’d be tough to advance.

In addition, not sure of the cause of death in the folks in the Cochrane study. Did they die as a result of iatrogenic effects of the therapy (cancer due to XRT, etc).

I am particularly amused by the “Death by any Cause” column. Excuse me if I’m wrong, but isn’t the percentage of death from any cause in humans 100%? The ugly truth about breast cancer is that a third of all women diagnosed with it at any stage will go on to develop distant metastasis. But more of the women diagnosed in stage 3 than those who are diagnosed in stage 1 will be accounted in that one third. Mammography may not lower the overall chance of death, but early detection is still the best chance to survive the disease. There are many ways that I’d rather die than from breast cancer.

Thanks for your post John. I believe active informed consent with shared decision-making is the way to go regarding whether or not a person decides to undergo “cancer screening”. Some folks may decide to do cancer screening, regardless if benefit (improved longevity) has not been proven. That’s their choice. But it should also be one’s choice to opt out of “cancer screening” (without pressure to comply) until such time that true increased longevity is proven by the screening test. Along the way (and to be incorporated into the shared decision-making process) is the potential to cause harm, which ALL screening tests may do (be it from the not-inconsiderable risk of perforation from colonoscopy, to false positive PSAs or mammograms that might lead to additional investigation/procedures that are not without potential consequence). BOTTOM LINE: Cancer screening is not the “win-win” situation it had previously been billed as …

Hi John, I reviewed the “2013” Cochrane review, page-by-page, and was stunned to find the data from the 1960s-(early 1980s) with one exception. I do hope you’ll take the trouble to read this:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/elaineschattner/2015/03/16/recent-studies-of-mammography-use-shockingly-old-data/

When it comes to screening, I think it is important to think about whether a given person can actually tolerate a chemo regimen if a cancer is caught too late for surgery alone to eradicate it.

If the person can’t tolerate chemo, catching such things early might be his or her only realistic option.

I can see how general recommendations are needed, though, if only to determine eligibility for insurance coverage, but I don’t think there really is a one-size-fits-all answer to the question of whether people should be screened or not.

Maybe some kind of decision making algorithm would be more helpful than recommendations based upon age alone.

Hello John

Nice of you to wade into the weeds of primary care! Of course we return the favor by taking care of lots of AFib patients. Perhaps you have seen H Gilert Welch of Datmouth? Read his NEJM article from 2013 “30 years of screening Mammography on breast cancer stages” Bottom line is despite an astronomical increase in DCIS and Stage 1 breast cancer, Stage 4 breast cancer has not changed. That is despite what makes.a nice story and in Maine Lisence Plate phrase “early detection saves lives” is simply not true.

Tom, I’m a huge fan of Gilbert Welch. I grew up in CT and vacationed once in Bar Harbor. I interviewed at Maine Medical Center for residency. And, for the win, I enjoyed DFW’s famous essay “Consider the Lobster.”

The interesting thing about AF care now is that it has come full circle–back to primary care. The overwhelming majority of my time spent with AF patients is used to discuss basic lifestyle issues. Attention to sleep, diet, exercise, relationships, alcohol moderation and stress management are central to the care of AF patients. Thanks.

Another interesting way to consider the impact of cancer screening would be in terms of its role in preventing or precipitating the accumulation of comorbid conditions in survivors over time.

It seems like the survival rates for the two groups looked pretty similar, but it would be interesting to consider how many people were chronically ill prior to, or following, an official cancer diagnosis.

I wonder how many people in each group were left unable to work or do their ADLs because of the side effects of chemotherapy or radical surgery, and I wonder how many retained or recovered function.

Some people are able to remain employed, or at least live independently during and after treatment, and others are not. Some of this depends upon the type of work each person does, of course, and things like age and treatment modality, but It would still be interesting to see the impact of screening on employment and the need for assisted living.

Many people have multiple bouts with cancer, whether it is caught early or late, and unless treatment is avoided completely it can take many, many years for someone to pass on.

Most people also really don’t want to know they have cancer and avoid the bad news like the plague.

However, as you have surely seen, even people who avoid their diagnoses until they are coughing up blood often eventually want to pursue every possible treatment. Everything is done, and for better or for worse, it is not unusual for these therapies to be at least temporarily effective.

It is good that there are tools available to help people to have a fighting chance against cancer, but I think that to some extent, it may have changed something that was once a question regarding mortality into one regarding morbidity. It would be interesting to see someone address this question in greater detail.