A new study published last week in an open heart journal changes the conversation about how patients and doctors think about and discuss preventive therapies–such as statins.

Dr. Richard Lehman may be the smartest doctor on Twitter. This is what he said:

This is a game-changer https://t.co/WgGdLlodbL

— Richard Lehman (@RichardLehman1) March 20, 2016

Most discussions about using statin drugs focus on a 5-10 year period. That’s not the right way to discuss these drugs. When we take a statin drug (or screen for cancer, or any other preventive intervention) we do it to live longer–not just 5-10 years.

Here is a link to the (free) study. The editorial is here.

Researchers from the UK used national registries to calculate death rates. They then devised a mathematical model to calculate the probability distribution of lifespan gains from statin interventions. They used the well-accepted relative (CV) benefits of statins of 20-30%. In the third part of the study, they surveyed random people in train stations, asking how they would judge potential benefit from the drugs.

Before I tell you the results, let’s consider how we currently explain statin benefits. In primary prevention, the absolute benefit from a statin drug (or cancer screening) is small. How small is a matter of debate, but what opponents to these therapies rightly say is that most people who take these drugs get no benefit. (If the NNT is 50, 49 get no benefit.)

The problem with that strategy is we use average estimates of benefit and translate them to everyone who would take a statin. You know that is not how life works. You could start on a statin, and come down with cancer, or get hit by a bus, or die from pneumonia the next year. Then the protective effects of statins never helped you.

The researchers sought to figure out the probability that statins (or any other prevention strategies) would help you over a lifetime. They used what’s called a Monte Carlo simulation. The model gives a range of probabilities for life-expectancy gains for each individual on primary prevention. “MCS is like throwing multiple dices at the same time – it is astrology with a dice.” The Monte Carlo simulation is explained well in this blog post. (Credit to Dr. Saurabh Jha, @roguerad on Twitter.)

The findings of this study changes everything.

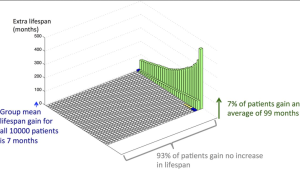

Lifespan gains are concentrated within an unpredictable minority. For example, men aged 50 years with national average cardiovascular risk have mean lifespan gain of 7 months. However, 93% of these identical individuals gain no lifespan, while the remaining 7% gain a mean of 99 months. See Figure to the right>

Another finding was that younger people benefit more from statins. That’s because, even though they are lower risk, they have longer to accumulate gains. Likewise, an older person has a higher risk of death from a heart attack, and in the old way of thinking, would benefit more from statins. This new model, however, predicts that an older person’s benefit would be lower because of competing causes of death.

Here is a nice quote from the editorial:

The study highlights the problem of focusing on disease-specific mortality rather than total mortality in the evidence used to recommend various medical interventions. The two measures are taken as similar but they do not necessarily follow each other as well as researchers would sometimes like to think.

The third finding from the study was that when people were asked what they preferred, they chose the lottery approach to lifespan gains. “Our survey illustrates that people often prefer a small chance of a large benefit over the certainty of a small benefit, even when the mathematical average gain from the former is smaller.”

This is my first crack at translating this important study. I learned of it this weekend. This changes the way we will talk with patients, and among other doctors.

Look at that graph: 93% of this group gets no benefit but the 7% gets tremendous benefit. It’s like a lottery to see if you will be the one who benefits.

One important weakness of this model, which was discussed in the paper, is that it only counts benefits of intervention. Statin drugs and cancer screening clearly have possible harms.

Stay tuned.

JMM

12 replies on “A new way to discuss statin drugs”

Statins have to be the most studied substance ever in the field of medicine. For something with such a low absolute rate of return it is astounding how they keep finding ways to spin it.

Looks just like a primary prevention ICD strategy, where most get no benefit but a minority have their lives “saved”.

I’d like to quote the very wise cardiologist, Dr. John Mandrola, who wrote this about statins:

“I’m growing increasingly worried about the irrational exuberance over these drugs, especially when used for prevention of heart disease that is yet to happen.” (April 2014)

The same wise doctor also wrote:

“If you don’t have heart disease, the best way to avoid getting it is so simple, so easy to understand, and so not up to your doctor. Pills should never be the basis of preventing heart disease.†(November 2011)

It seems that the times they are a’changing ….

Are they including the lengthy and serious damage that today statin’s cause into their “benefit projections?” I recently read they are working on a new class that would minimize the risk of statin myopathy but based on my group of aging friends and family the current class of statins have so many side effects they reduce the quality of life in many(or damage the liver so most of us are tossing them along with the flu shot). So, do we suffer taking a drug that may or may not increase our life(do they factor in quality of life?) or do we make sensible changes to our lifestyle? Cut the junk, walk more, embrace life and live well. I think sensible changes are less risky and more likely to encourage a better outcome regardless of “length” of life.

This (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15271005) is an interesting and related viewpoint where the author argues that in order to ethically offer a primary prevention “treatment”, we must *assume* that every patient we treat enjoys a reduction in risk of some negative outcome. According to Dr. Brennan, that’s the only way to interpret the results of drug trials. The reality, which we all know, is that most often, the risk reduction is concentrated in only a small minority while the majority get no benefit or, perhaps, harm.

So long as patients are well informed, I don’t see any ethical issue with such strategies. The tricky part, which your article rightly raises, is how to make sure your patient is well informed when the information giver has to be digesting and relating rather complicated stuff…

As with cancer screenings, the evidence indicates a need for more effective risk assessment.

As with the USPSTF statement on PSA screening for prostate cancer, the assessed endpoint is cause-specific death. Unlike the USPSTF, “harms” resulting from treatment are not assessed.

Neither address the possibilities that there are benefits outside the primary endpoint (death).

I am suspicious of the claim that 7% of [male] primary prevention statin users, over a lifetime, will be “saved” from a particular date of death by statin use; this is a large enough fraction that you would think there would be some hint of benefit in long-term trials. Most of those trials had zero difference in life expectancies, with the modestly fewer fatal heart attacks being balanced by the modestly fewer cancer and violent deaths.

The suggestion that statinization for life provides the “most benefit” certainly serves the manufacturers, but how about the patients? Let’s suppose that I will agree that when I am 65, my annual risk of heart disease is high enough that the benefits of statins outweigh the diabetes, cognitive risks, muscle damage, etc. But when I am 50, my annual risk of natural disease is small enough that the annual risk of toxicity outweighs it. Why should I start popping pills with a lousy risk-benefit ratio then because it will be better later? And where would that stop? Could the claim not be made, equally without evidence, that my risk of having a heart attack at 66 could be even lower still if rather than statinizing from 65 on or even 50 on, I started statinizing at 20? Can anyone begin to estimate the total burden of toxicity from truly lifelong statin use? If the heart attacks prevented are supposed to be viewed as continuing to rack up over most of a century, so too will be the cases of diabetes caused.

drat – obviously, in the first paragraph, I mean modestly MORE cancer and violent (including accidental) deaths.

Recent medical-thought suggests that those with a zero CAC score get a free pass: no statins necessary, risk score notwithstanding.

How many of the greatly “benefitted” had no “need” of a statin in the first place?

Is the game changer obsolete? Should we have a conversation about statin therapy without including the CAC score as part of it?

Seems like the old saying about the weather rings true for statins and BP meds advice. “If you don’t like it, hang around for 15 minutes, and it will change”. It does confuse this poor layman.

Dietary advice follows the trend as well.

I’m waiting for high fructose corn syrup to be declared the new wonder drug, especially when fortified with trans-fats.

I may be too dense but I fail to understand any game changing this “study” accomplishes.

As a clinical cardiologist working in the trenches to prevent sudden death from CAD, I focus on identifying those who stand to benefit the greatest from statin therapy and those who are unlikely to benefit and I don’t see what this paper adds.

The comment that “Lifespan gains are concentrated within an unpredictable minority” is only true if you ignore methods for identifying coronary plaque noninvasively, either in the carotids (vascular) or the coronaries (calcium scan).

The minority that benefit from primary prevention are actually the ones with advanced or premature atherosclerosis which is asymptomatic.