Stanford economist Raj Chetty and coworkers published an important paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association this week. It’s free.

They looked at the association between income and longevity in the US.

The results will disrupt a lot of what you might have thought about healthcare.

- The first finding was not surprising: higher income associated with longer life. The differences were immense–almost 15 years from lowest to highest income for men.

- The second finding was that inequality in life expectancy increased over time. Between 2001 and 2014, life expectancy increased by 2.34 years for men and 2.91 years for women in the top 5% of income group, but by only 0.32 years for men and 0.04 years for women in the bottom 5%.

- Life expectancy in the low-income group varied a lot based on geography. The poor in some cities did much better than poor in other cities.

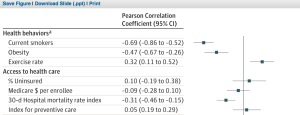

- The fourth finding was the most important for the American concept of healthcare. The researchers found that geographic differences in life expectancy for individuals in the lowest income group were significantly correlated with health behaviors such as smoking, but were not significantly correlated with access to medical care, physical environmental factors, income inequality, or labor market conditions.

Read that again. Access to healthcare did not correlate with life expectancy.

This is exactly what Dr. David Nash (Thomas Jefferson University) told the American College of Cardiology meeting two weeks in Chicago. In the plenary session at ACC, Nash used the example of health outcomes in counties in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia county, the home of five world-class medical centers, had the worst population health outcomes.

I summarized Nash’s lecture in this post: Pivoting to Prevention and Population Health Will Not Be an Easy Pill to Swallow

Here is an except of my piece:

Zip code is the most important biomarker of health. Forget cholesterol numbers, blood pressure, and HbA1c; where one lives is their health destiny. Nash showed a map of Pennsylvania counties color-coded by health outcomes. Philadelphia County, the home of five major medical centers, ranked dead last.

Access to medical care plays a small role in determining health outcomes. Nash said the key determinant of a population’s health is not gleaming new medical centers, but individual behavior. He cited the recent study[1] showing only 3% of Americans live a healthy lifestyle (being sufficiently active, eating a healthy diet, being a nonsmoker, and having a recommended body-fat percentage).

I’ve often said that if I had another blog, it would be called, Health cometh not from healthcare.

The factors that correlated with better longevity among the poor in different cities: Higher numbers of immigrants, higher home values, government expenditures, population density and % college graduates.

It’s about time Americans wake up to the fact that the medical profession does not determine a population’s health.

Individual behaviors made the difference. Look at Figure 8 from the Chetty paper:

Smoking. Obesity. Exercise. Those are the factors that made the difference. Not preventive care.

Population health means having more parks, walkable neighborhoods, schools and immigrants, not medical centers and screening vans.

The medical profession does best when we care for sick people. Not having sick people seems best accomplished by society as a whole.

JMM

2 replies on “Access to healthcare does not deliver health”

About two and a half years ago, Elizabeth Bradley and Lauren Taylor discussed very similar concepts in their book, “The American Health Care Paradox: Why spending more is getting us less” (public affairs press, 2013). In it, they review several data sets including one that suggests the US spends much more on “Health Care” than Social Services. They argue that public sector social service spending might accomplish what you are suggesting.

Dr. Mandrola,

The following comment pertains to your recent Medscape piece: “Pivoting to Prevention and Population Health Will Not Be an Easy Pill to Swallow”, which you’ve also linked to here today.

Thank you for writing this enlightened, and enlightening, article. However, I am unsettled by one of your stated reservations about implementing life-style based disease prevention.

You wrote: “It influences the doctor-patient relationship. I am a vigorous advocate for lifestyle measures as therapy, but doctors are not their patients’ mothers. We live in a free country. Yes, I can counsel my patient on healthy behaviors, but ultimately, it’s up to people to choose what’s best for them”.

Methinks your statement is a bit of an apologia, wherein doctors may find a pat excuse to opt out of their part of the heavy-lifting that lies ahead. I agree, most physicians probably don’t feel they are in the business of mothering their patients. But, on the other hand, the doctor-patient relationship is surely one of the most inherently paternalistic relationships imaginable. Moreover, when it comes to the matter of medication adherence, physicians are not the least bit hesitant to hector, lecture, and brow-beat patients about being responsible for taking all of their medications every day, exactly as prescribed — for the rest of their natural lives. Strange, that doctors would not feel free to be equally insistent with their patients about taking responsibility for making lifestyle changes to prevent and treat our escalating epidemic of chronic disease.

Granted, patients may choose to ignore any medical advice they are given. That, however, is no excuse whatsoever for failing to give the advice — no less so for adhering to healthful lifestyle habits than for adhering to appropriate medication. Indeed, if physicians lectured more effectively about Therapeutic Lifestyle Change (TLC) we might all find ourselves in the fortunate position of having fewer lectures about taking pills.