Yesterday I posted the four most important questions to ask your doctor.

Let’s apply those questions to a typical scenario:

Whether or not to take an anticoagulant drug for prevention of stroke in the presence of AF.

We need a typical patient. For this example we will pick a typical CHADS-VASC 2 patient.

- 65 year-old male with treated high blood pressure. (One point on the CHADSVASC scale for BP and age > 65.)

- 60 year-old female with treated diabetes. (One point on the CHADSVASC scale for female gender and one for diabetes.)

Question 1: What are the benefits of taking anticoagulants?

The only known benefit of the anticoagulant drugs (warfarin or NOACs) in AF is to prevent stroke or what’s called a systemic embolism–a clot from the heart that blocks an important blood vessel, say to the kidney or spleen or leg. Strokes are much more common.

The best resource for this exercise is the decision aid from the NICE – National Institute for Health Care Excellence (UK).

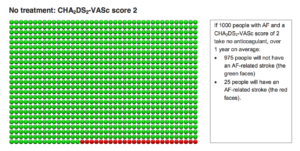

The two diagrams below are from the decision aid. The first group of smiley faces depict the risk of stroke without an anticoagulant. If 1000 people with AF and a CHADSVASC score of 2 take nothing, over 1 year, 975 people will not have an AF-related stroke (the green faces) and 25 people will have an AF-related stroke (red faces).

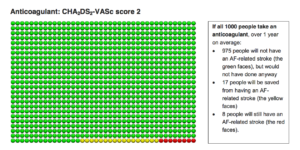

The second diagram depicts the results of taking an anticoagulant for these same CHADSVASC 2 patients.

Here, if 1000 people take an anticoagulant, over 1 year, 975 people will not have a stroke, but would not have had one anyways (green faces); 17 people will be saved from an AF-related stroke (yellow faces), and 8 people will still have a stroke (red faces.) (Note: no drug is perfect.)

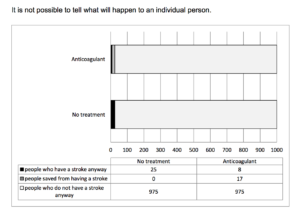

Another way of depicting the benefits is here:

In summary:

The statistical benefit of taking an anticoagulant is about 17 in 1000 per year, or about 1.7%. More than 97% of patients get the same effect–no stroke–whether they take the drug or not.

Question 2: What are the harms of taking an anticoagulant?

The harm from an anticoagulant drug is bleeding. Note that anticoagulant drugs don’t cause bleeding, rather, they intensify bleeding that is present for another reason. (Say an ulcer or diverticulitis or kidney stone.)

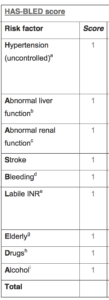

The risk of bleeding from the drugs can be estimated with an algorithm called the HAS-BLED score. (Pictured to the right.)

We picked a low-risk patient scenario before so let’s pick a patient with HAS-BLED score of 2.

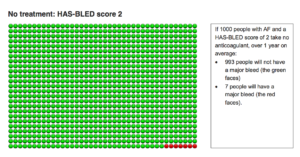

Using the smiley faces diagrams, here are the risks of bleeding on and off anticoagulants for a patient with two of the HAS-BLED factors.

The above diagram shows that if 1000 people with AF and a HAS-BLED score of 2 take no anticoagulant, over 1 year, 993 people will not have a major bleed (green faces) and 7 people will have a major bleed (red faces).

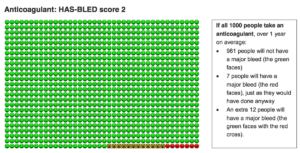

The picture below shows that if 1000 people take an anticoagulant over 1 year, 981 people will not have a major bleed (green faces), 7 people will have a major bleed (red faces), just as they would without an anticoagulant, and an extra 12 people will have a major bleed (the green faces with red crosses).

In summary:

The statistical harm from anticoagulation in this group is a net increase in 12 per 1000 or 1.2% increase in bleeding. More than 98% of the patients in this group who take an anticoagulant do not suffer a major bleed.

Question 3: Are there safer simpler options?

Probably not. Many people think aspirin is an option. The thought being that aspirin provides some stroke prevention with a “milder” anticoagulant, less apt to cause bleeding.

The European guidelines strongly recommend against use of aspirin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. They cite no definitive study showing benefit, and plenty showing harm from bleeding. North American guidelines admit that 5 of 6 randomized trials comparing aspirin to warfarin were negative, but one study suggested a mild risk reduction of aspirin versus placebo.

I like to show the BAFTA trial. This study of nearly 1000 elderly AF patients found that the risk of major bleeding was not different between aspirin and warfarin. I, therefore, side more with the European guidelines. Aspirin confers significant bleeding with either no or minimal stroke prevention effects.

4. What happens if I do nothing?

This is easy. For the patients above, who have two risk factors, the green faces depict what happens if they do nothing. The most likely scenario is that they will not have a stroke (approx 97%) and not have a bleed (98%).

The North American AF treatment guidelines grade the strength of their recommendations. They give the strongest rating for shared decision-making surrounding the choice to take an anticoagulant drug or not. It’s up to you.

*******

Four caveats:

Caveat 1: One is that doctors think the stroke prevention/bleeding risk tradeoff noted above is a good one. You may quibble with it. You might say the 1.7% risk reduction in the probability of stroke is balanced by the 1.2% increased probability of a major bleed.

What I explain to patients is that strokes are much worse than major bleeds. Bleeding is scary and to be avoided, but bleeding rarely leads to disability like strokes. Most patients who suffer bleeds leave the hospital the same person they were on admission. Strokes, on the other hand, can leave people without speech, thinking, swallowing or movement.

Caveat 2: The numbers listed above vary. For higher risk patients (CHADSVASC >2) the risk of stroke is higher and the risk reduction of anticoagulants is greater. You can click on the NICE decision aid and you will find different scenarios for higher and lower risk patient groups.

Caveat 3: Drs. Quinn and Singer, from the Beth Israel Hospital in Boston, have published a disruptive study that questions the reliability of the numbers posted above. The numbers used in the decision aid come from Northern European registries. What the BI authors showed is that different populations may have different baseline stroke risks–and if that is true, it calls into question the point at which we say the net benefit of anticoagulation outweighs harms. (I wrote about this study. My post was titled: Big Blind Spot in the Guidelines.

Caveat 4: NOAC drugs change the decision a little. Multiple clinical studies have compared NOAC drugs to warfarin. In brief, as I wrote in 2013, the two classes of drugs–warfarin and NOACs–perform within 1% of each other. The slight nod, however, goes to the NOAC drugs.

JMM

24 replies on “Should You Take an Anticoagulant for AF? — Applying the 4 questions”

One thing not mentioned here is potential OTHER benefits of aspirin, e.g. related to colon and other cancer prevention. Unusual that this should be considered but in this case it might be a factor?

Though if aspirin is COMPLETELY ineffective for preventing stroke, not relevant here. But if somewhat effective, might be relevant?

Dr. John, Thank you for this informative article. It is very hard to make a decision about whether to take an anti-coagulant or not. There is still the issue of what these do to the immune system. There are new studies right now to check the effects of the NOACs on the immune system. As soon as my husband was put on Pradixa he got viral infections. Apparently clotting is related to the immune system working properly. Can you please comment on this aspect? I have never seen this discussed as another possible harm from the anti-coagulants, especially the newer ones.

I would really appreciated discussion about the harmful effects of the anti-coagulants on the immune system. There are valid and reliable studies showing clotting is important for the immune system to work properly. So it’s not just the bleeding risk with the anti-coagulants…

That’s an interesting (and worrying) point. As I am a female rising 75 with PAF I am struggling with the decision whether to anti-coagulate. Up to now, I have favoured the prospect of NOACs over warfarin because, among other considerations, it seems to me that we must surely need vitamin K. It had not occurred to me that anti-coagulants that spare vitaminn K might be harmful too, apart from the obvious bleeding risk.

The studies are actually on the NOACs affecting the immune system negatively. There are plans to study warfarin as well to see if there is also a negative effect on the immune system too. I sure wish Dr. J. and others would address this as well as the bleeding risks.

The possibility that the NOACs adversely affect the immune system is particularly worrying to me as the level of my neutrophylls (white blood cells that help the immune system) has for years been hovering between a little too low and just about satisfactory. Low neutrophylls are recognised as a possible side-effect of Flecainide, which I have been taking for years. I have noticed that despite an extrmely healthy lifestyle I do seem to get ill every winter. It sounds as if adding a NOAC to Flecainide could make that situation worse.

I think you’re right about the need for VItamin K, specifically Vitamin K2. Most GPs and medical professionals I’ve spoken to seem unaware of it’s existence, and research is only now highlighting how important it is, and the negative effects of long-term use of Vitamin K antagonists like Warfarin. I’ve seen the effects first hand with a family member who’s been on Warfarin for 20+ years, which prompted me to look into the literature over the last few years. The good news at least, it appears Warfarin induced damage may be reversible.

Warfarin and Vascular Calcification – Jun 2016

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26714212

“Use of Warfarin is associated with an increase in systemic calcification, including in the coronary and peripheral vasculature.”

Regression of warfarin-induced medial elastocalcinosis by high intake of vitamin K in rats

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17138823

“…whereas during the high–vitamin K diet (both K1 and

K2) the vascular properties that were lost by Warfarin-induced

calcification were restored.”

The following Japanese study published in December 2015 showed lower stroke rates in patients with paroxysmal AF:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26514188

It states that there have been other studies coming to the same conclusion. I’d very much appreciate comments on this.

Alexandra, yes you are right. Over the past few years, ample research has found that the degree of stroke risk is dependent on the degree of AF. And yes, that fact should probably factor heavily into decisions about anticoagulation.

Dr. Mandrola wrote a piece about these “potentially practice-changing data” just a couple of years ago, as I noted in my prior comment below. Here’s the link again to that Dr. Mandrola article from Medscape, November 17, 2014: “In Terms of Stroke Risk, Not All Atrial Fibrillation Is Created Equalâ€. Link: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/835038

Dear John,

I’m MD and asymptomatic afibber . My age is 66 and I have treated hypertension. So the dilema whether I should anticoagulate or not is very compelling problem for me.

My impression is that current risk score methods are based on insufficient number of factors. Lets take to examples:

The trivial missing factor is the genetics. My afib is a combination HCM and athletic heart. Both my parents were afibbers. My case as clinical appearance is very different to my mother and resembles my father’s asymptomatic case.

The second example is the CRP. According to a recent publication CRP might be responsible geographic and racial differences:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27712649

Not surprisingly the ROC curves of the current scoring schemes are far from the “good”.

So my feeling is that elaboration of better scoring systems based on more factors is an urgent need.

Kind regards:

György

This was very helpful but still doesn’t quite help me. I am 66 and female- score 2. No other risk factors. Paroxysmal AF only induced by exercise with heart rate over about 150. Heart rate controlled with metoprolol. The cardiologist says take Eliquis. Would you? Seems like the risk of bleeding outweighs the risk of stroke for me. Am I missing something here?

Would love to hear comments on this and the studies cited above for paroxysmal AF.

Nice post Dr John! While clearly (as you emphasize throughout) there are lots of patient variables that will alter the estimations for potential risk vs benefit of anticoagulating or not for AFib — I think the message is clear from your detailed (and very well documented) discussion that potential benefit from anticoagulating low-to-moderate risk patients, when considering potential drawbacks (bleeding) of such treatment — is less than has been generally appreciated. You also make clear that if nothing is done for such low-to-moderate risk patients — that the overwhelming majority will not develop a stroke. THAT is an important message, that I do not think is adequately appreciated by the medical community. This is not to say that clinician efforts to encourage anticoagulation of patients with AFib and without contraindications for anticoagulation should not be made (because they should be!) — but rather to realize that the data do not support as overwhelmingly a positive message for anticoagulation as is generally thought … Given that, fully informed patient preferences should continue to play an important role in the decision-making process, and such preferences should be respected and accepted by their treating health care team. THANKS for putting this data together! P.S. I was unable to enlarge your figures by clicking on them in either of the 2 browsers I just now tried — so would be great if there was a way to enlarge your red & green face figures.

Have had three lone AF episodes over 10 years – one roughly every three years. been about three years since my last. Medication returned me to normal rhythm after about 16 hours each time. Am 54 yo male. Now about 30 pounds lighter than when had AF each time. Exercise regularly now; not then. Eat LCHF now; not then. Quit Pradaxa after last episode. Have a friend who just had stroke due to AF. Very sad. He lived. But cannot speak or organize thoughts. Troubling.

We know the angst of the dilemma of to coagulate or not. My husband also has PAF and has been advised by some doctors to take the anti-coagualtants. Another doctor did not want him on them. He was on Zarelto for a while and had a small early colon cancer bout which was dealt with ok because it was caught early enough. However we then found out that Zarelto was adversely affecting the immune system (interacting with tamulosin medication) and may have contributed to the development of the cancer. He was immediately taken off this and was on nothing for about a year. He was then put on Pradaxa; as soon as he took it he got a viral infection. He stopped taking this against some of the doctor’s advice. We researched these NOAC’s and found they all pretty much affect the immune system. And Warfarin can affect the cardiovascular system negatively and is supreme pain to manage. So what’s a person to do? We are choosing to focus on lifestyle factors we can control to lessen the stroke possibilities – no anti-coagulants. Simple things such as a whole foods plant base diet with no animal foods, very low sodium intake, no alcohol or tobacco, and moderate exercise. We are learning that the medical establishment has not given enough attention to the power of lifestyle changes and foods in all health issues. After his latest A-fib episode this past Oct., my husband looked at his sugar intake (his triglycerides were a bit high) and eliminated this. This has made a world of difference. There is power in lifestyle changes!!

Thanks for the reply. Yes, I too have chosen the lifestyle change approach. Still, as you say, it is a dilemma. All the best to your husband.

It is quite a dilemma.

Having known several friends who suffered major brain bleeds on anticoagulants, one of whom died, and the other who lost memory and cognitive functioning, makes me quite concerned.

Another caution came from a retinal specialist who notes the not often mentioned issues he’s seen with bleeds in the eye causing major vision problems and loss.

All not so comforting to a patient faced with the decision.

In my case, Pradaxa was an evil experiment in stomach and esophagus problems, major bruising and skin peeling off (yes, skin peeling off).

Xarelto was much better tolerated. Fortunately, as I’m now not having afib following ablation with med chasers and lifestyle changes, I’m not worrying about anticoagulants, but if afib ever returns, I’ll have that decision to wrestle with again.

Also be aware that a huge number of medications and supplements do not play nicely with anticoagulants, and you have to weigh the risks of not taking other vital drugs or supplements or even certain healthy foods when on the anticoagulants.

A patient should also investigate whether he is really a “CHADS2 2” or should consider himself a “CHADS2 1.5” or less, or contrarily “2.5”. Let’s consider he gender-based fearmongering of the CHADS2VASC. In two studies of AF patients, females were at substantially higher risk than males only in the first year after diagnosis or only after age 70. It is known that without AF, women have slightly higher stroke rates than men; this is not a reason to put all women on rat poison. The correct question is whether a woman’s absolute stroke risk is high enough that in a male patient it would be considered to justify dangerous and burdensome prophylaxes. If a 40-year-old female with lone AF really had the same stroke risk as a 50-year-old male with lone AF, it is still the case that anticoagulants are more likely to gork than to “save” her.

Now on to the other mentioned characteristics. “Treated hypertension” gets a point just like uncontrolled hypertension (SBP > 140). People who are pounding blood pressure pills for the explicit purpose of “lowering their stroke risk” might wonder about this, and should look up the Framingham data that are the sole rationale for that point. When stroke rate is plotted against blood pressure for treated and untreated SBP separately, the numbers are identical at low values (170). In the midrange, they diverge, so a person with treated SBP of 140 has a higher risk than a person with a natural SBP of 140. (This will be even more true if he’s been bulled into beta blockers, which may actually increase stroke risk in the elderly.) But the curves don’t separate enough to give the treated person a risk equivalent to SBP of 140 until a treated SBP of 130 or so. If your ologist is drugging you down to 85/55, like happened to my husband for a year or more after his malpractice cascade, you should refuse to accept a CHADS2 point for “hypertension”.

As for “diabetes”, be wary of quoted risk ratios and stroke rates from older literature. (This is always true given the decline in stroke among older Americans.) The studies validating CHADS2 were done in an era when diabetes was defined as either actual symptoms or a fasting blood glucose of over 140. Then, by the action of a corporate money-dominated expert panel, it became glucose over 126. Now it can be HbA1C over 6.5% (which can be affected by vitamin deficiency, by the way), even if your glucose is never seen to exceed 100. Is that “diabetic” the same as the one with fasting glucose >140? If the female patient wouldn’t have been diabetic in 1990, she can probably assume her stroke risk is a little lower than, say, a male whose CHADS2 score of 2 derives from a prior stroke.

Sorry, use of the “greater than” and “less than” signs caused a piece of my comment to be deleted. Stroke risk is identical for treated and untreated blood pressure when the SBP is low – “less than” 115 – or high – “greater than” 170.

I realize that I underestimated the gynophobic nature of the CHADS2VASC in offering the hypothetical of a woman’s risk being equal to that of a man’s a decade older. This implies that female sex doubles risk, since stroke risk typically doubles per decade of age. In fact, the CHADS2VASC is worse than this, because it would give one point to that 40-year-old woman but not to a 64-year-old man. Is being female worse than being a quarter-century older? Nope, it is not.

Dr. Mandrola, shouldn’t the anticoagulation decision also be based on the TYPE of AF that a patient has?

On November 17, 2014 you did a great article on that particular subject for Medscape: “In Terms of Stroke Risk, Not All Atrial Fibrillation Is Created Equal”. Link: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/835038

You cited a number of related recent studies that consistently contradicted the prevailing dogma that all types of atrial fibrillation (AF) confer an equal degree of stroke risk. In fact, these new studies found that the degree of stroke risk is dependent on the degree of AF. For example: “Researchers from Canada, Germany and the Netherlands analyzed rates of stroke in the 6563 aspirin-treated AF patients included in the ACTIVE-A/AVERROES database according to AF presentation. They found yearly stroke rates were 4.2%, 3.0%, and 2.1% for patients with permanent, persistent, and paroxysmal AF, respectively”…

You concluded: “Now there looks to be compelling data that are consistent through multiple studies, using contemporary patients, and hold up in both nonanticoagulated and anticoagulated groups…Consider two patients with a CHADS-VASC of 1 or 2. One has 30 minutes of AF weekly and the other has permanent AF. Are the risks the same? Shouldn’t the type of AF factor in the risk/benefit decision of anticoagulation? These studies suggest the answer is yes.”

It would be great to hear any further thoughts that you have on this topic — especially because you are promoting use of the CHADS-VASC risk calculator which fails to differentiate between different types of AF — and AF treatment guidelines also fail to distinguish different types of AF. In the meantime, one can only hope that patients will fully inform themselves and decide accordingly.

It is a really good question. Stroke risk based on type of AF is an area of uncertainty.

I am certainly not promoting use of CHADS-VASC score. As a predictor it is only a bit better than a coin toss–ROC about 0.6 with coin flip 0.5.

I used the CHADSVASC in the example only as a starting point to discuss how to apply the four questions.

Dr. John, now I am quite confused! On what basis then do you make a decision whether to recommend the anti-coagulants or not???

Thanks for any clarification.

As an avid follower of Dr John’s writings, I hope I have correctly understood that he precisely does NOT aim to recommend any course of action to patients, rather tries to present them with facts and considerations to give them a fair chance of making good decisions for themselves.

Dr. John, I am wondering if a person with PAF could possibly take a blood thinner such as Pradaxa ONLY when in active A-fib or when the heart is behaving irregularly/erratically? Is it not possible then to just medicate with the anti-coagulant at high-risk times rather than all the time?

Just a short note.

Genomic prediction resulted in 0.86 ROC:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2752697/

Ramoni et al,

Predictive Genomics of Cardioembolic Stroke

Stroke. 2009 Mar; 40