It has been awhile since I wrote about catheter ablation of Atrial fibrillation (AF).

It’s time. Things have changed—for the better.

But you wouldn’t have guessed this if all you read were recent headlines. Medpage Today says AF ablation is dogged by complications. TheHeart.org calls complications after AF ablation not uncommon.

These stories summarize the findings of this slightly jarring real-world report on 4156 AF ablations done in California between 2005-2008 and published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC).

The researchers from San Francisco report four main findings:

- Acute complications occurred in 5% of AF ablation procedures. The good news was that almost half of these were minor vascular issues. The bad news included a high number of heart perforations (104) and stroke/TIA (13).

- At 30 days, the complications looked worse. Almost 10% were re-admitted, 5% had a stroke and nine patients died.

- By two years, approximately 30% of patients were re-hospitalized for a recurrence of AF/flutter, yet only 17.4% of patients were ablated a second time—a possible indication that many were ablated in inexperienced centers.

- AF ablation was often done in low-volume centers, and hospitals with the lowest volumes fared worse.

As a doctor who spends a great deal of time explaining the well-known risks and less-than-perfect outcomes of AF ablation, this news seems, well…not very much like news. Overall, the complications were about the same as reported in prior studies, though the slightly higher rates of heart perforations and stroke were a little troubling. (See below for limitations of study.)

By far, the most provocative finding of this investigation, one highlighted by Dr David Haines in an editorial, was that experience mattered. That’s a tough topic to talk (or blog) about. Dr Haines did not shy away from the controversial topic. He directly described two challenges of forming specialized centers of AF ablation: that hospitals are incented to grant privileges to doctors that claim proficiency and that specialists may not refer patients to other specialists. (I have witnessed this for years—as patients in my city are referred to centers hundreds of miles away for a procedure that is routinely done in our competing hospital.)

Dr Haines concludes by admonishing AF ablation programs to track their outcomes by collecting real data after ablation. He warned that given the high costs of AF ablation, ‘if healthcare providers do not regulate themselves, it is inevitable that outside bodies will impose regulation upon us.â€

The study had significant limitations.

1.) The most important limitation is that the data is outdated. Since 2005-2008 AF ablation has greatly improved. There are a number of factors leading to these gains. Foremost is the rapidly accumulating experience base of doctors and hospitals. My experience is instructive: During 2005, our center (my colleague and I) were doing 3-4 ablations per month, whereas now we may do 3-4 in a day. AF ablation used to make everyone nervous; now it is part of a normal day. The staff have even grown to like AF ablation, as, for the most part, it is predictable. (It’s rarely fast and easy, but it’s also rarely an all day slugfest.)

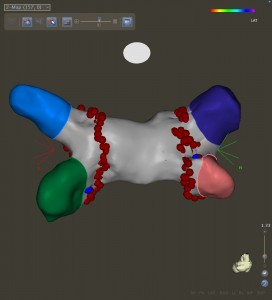

And yes, all this experience makes a huge difference. We doctors have learned to ‘feel’ the feel of the left atrium. How hard to push, how much to torque and how long to burn are all neural pathways developed only from doing. The staff’s experience has also contributed. Nurses come to understand the importance of monitoring blood-thinning and how to quickly recognize complications; our technicians learn tricks to keep the complicated software and hardware of the lab running smoothly.

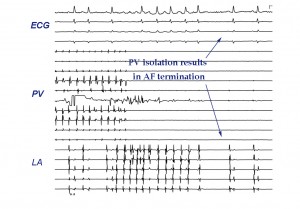

2.) The second limitation stems from the fact that the researchers could not tease out the specific technique used to ablate AF. They knew a patient had AF ablation, but they could not tell whether (or what) additional ablation was done. Additional ablation beyond the standard PVI lesion set may be an important risk factor for complications and paradoxically, some believe, may actually lower the success rate.

The best way to do AF ablation remains both unknown and hotly debated among leaders in the field. Questions like, when should right atrial flutter lines be made, should the SVC be isolated, should one look for extra-pulmonary triggers with adrenaline infusions, or in more advanced cases of AF, should additional lines be made, all remain unresolved.

What’s more, the most recent approval of, and increasing acceptance of cryo-balloon PV isolation has only added to the uncertainty about AF ablation. How does the cryo-balloon compare with radio-frequency ablation? What part of the cryo learning curve is your doctor currently on? Can data from clinical trials of cryo-balloon, which were done in specialized centers, be generalized to the real world?

These are all tough questions that studies looking at results from 2005-2008 cannot answer.

Though it is agreed that AF ablation always includes PV isolation, the technique could not be called standardized. Given this disparity, along with the rapidly evolving technology of AF ablation, it’s hard to make sweeping statements on the safety and efficacy of a procedure that’s moving so fast.

In summary, I can say this…

AF ablation appeals to patients because of its treasure: the improved quality of life that comes from the relief of AF symptoms. It is for each patient to decide whether the journey to this treasure is worth the risk.

And the job of the AF doctor: to explain the journey and then be a skilled guide.

JMM